Pacific Southwest, Region 9

Serving: Arizona, California, Hawaii, Nevada, Pacific Islands, 148 Tribes

Tribal Accomplishments, 2009

Protecting Tribal Lands

Bottom: Santa Ynez, post clean-up.

by the Washoe Tribe and the Nature

Conservancy at the West Fork of the

Carson River.

Pollution Prevention and Solid Waste

EPA’s approach to waste management has evolved over the past 25 years to reflect growing tribal interest in the entire waste cycle, recognizing that open dump remediation is only successful with a strong focus on waste collection and minimization.

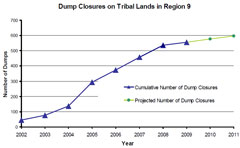

Tribes have been partnering with EPA’s waste program since 1985. Today approximately 80% of tribal communities have adopted or implemented integrated solid waste management strategies. These strategies include the closing of over 500 open dumps, pollution prevention and resource conservation projects, and the creation of appropriate disposal facilities. Tribes continue to improve their management practices through these measures and by developing comprehensive waste management plans. Seventy-seven tribes in the Pacific Southwest Region have created a tribal solid waste management plan since 1977.

Over the past 25 years, in addition to providing support for solid and hazardous waste management and cleanup, EPA’s Tribal Solid Waste Program has evolved to include:

- Circuit Riders who visit tribes and provide assistance by documenting open dumps with Global Positioning System (GPS) technology and digital photos. This information is used by EPA and the Indian Health Service to make it easier for other federal agencies to provide funding for waste programs.

- Resource Conservation Fund grants to support tribes in their pursuit of innovative ways to reduce, reuse, recycle and manage materials to reduce waste.

- Federal enforcement and facility inspection at open dump sites on tribal lands using a new enforcement authority under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) Section 4005(c)(2). Since 2006 EPA’s Tribal Solid Waste Program and RCRA Enforcement Office have collaborated with tribal governments to successfully use RCRA to close open dumps and assist tribes in enforcing their own waste regulations.

- Tribal Green Building to provide stronger and more diverse technical assistance to tribes pursuing sustainable green building and clean energy projects. Specifically, EPA assists tribes in leveraging available technical and communication resources, and facilitates multi-agency dialogue on tribal housing.

A few notable recent tribal accomplishments include:

Legacy Dump Site Cleanup on the Santa Ynez Chumash Reservation

In 2009, the Santa Ynez Chumash Environmental Office worked with Chumash Tribal residents, the Chumash Fire Department and volunteers from the U.S. Army Reserve to clean up a legacy dump site in one of the most pristine natural areas on the Chumash Reservation. A total of 19 tons of debris, 24 cars and motorcycles, a dozen white goods (large appliances like washers), and 30 car batteries were removed. This dump site ran along the Zanja De Cota Creek, a perennial stream that serves as the sole source of drinking water for the tribe. Contaminants from the dump site could have drained into the creek during rainstorms, adversely affecting water quality and wildlife. By removing all buried and visible debris the tribe eliminated a major source of polluted runoff. Soil testing to determine if there is any additional contamination will be completed later this year.

Moapa Pesticide Clean Up

In June 2009, the Moapa Band of Paiute Indians requested EPA assistance in dealing with pesticides that had been abandoned in a storage shed on their reservation. Noxious fumes coming from the shed during hot weather concerned the tribe, since the abandoned pesticides were close to homes, the tribal health clinic, and the preschool. Further, the shed was only 100 yards from an irrigation ditch, and about 500 yards from the Muddy River.

EPA’s Emergency Response Team (ERT), in coordination with the Tribal Solid Waste Team and the Moapa Band, conducted an initial assessment, finding about 70 gallons of pesticides, some of which had saturated the shed’s cement floor. The ERT safely removed, transported and properly disposed of all the pesticides.

Salt River Pima-Maricopa Removes Hazardous Waste

Using tribal funding, the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community’s (SRPMIC) Environmental Protection and Natural Resources (EPNR) Department removed over 2,000 gallons of hazardous materials collected from the community. EPNR staff ensured all materials were properly identified, characterized, labeled, and manifested for transport on a 53-foot tractor trailer. Everything was then hauled away for proper disposal. The EPNR, Salt River Fire Department, and SRPMIC Administration are involved in ongoing management, infrastructure development, and health and safety training. EPA hazardous waste funds will be used to help develop a hazardous waste inventory and coordinate future collection events.

Fallon Paiute-Shoshone Tribe Used Oil Recycling Program

In November 2008, the Fallon Paiute-Shoshone Tribe Environmental Protection Department (EPD) started a Used Oil and Oil Filter Recycling program with funds from EPA’s Hazardous Waste Management grant program. This recycling program was developed to accept used oil and oil filters from tribal “do-ityourself” oil changers and to dispose of the used oil by burning it in a used oil furnace, which now provides heat for the tribal auto shop. Continued participation in the program is expected to be high due to the enthusiastic response to the Motor Oil Assessments conducted by the EPD, and continued community education on the dangers of improper disposal of used oil.

Underground Storage Tanks Program Office (USTPO)

The Underground Storage Tank (UST) regulations were promulgated in 1988. During the initial years of the program, there was little UST activities with tribal partners. The first grant, for $80,000, was awarded to the Navajo Nation in 1997. This was a demonstration grant, and the key project goal was to complete an inventory of all UST sites on the Navajo Nation. As the UST program developed, tribes were often on the fringe. They were not included in national tanks conferences, inspections were sporadically conducted, and tribal staff received minimal training to conduct compliance inspections and oversee tank installations and removals.

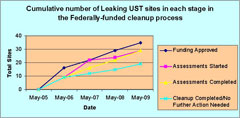

Since 1997, EPA has expanded funding to pay for Leaking UST cleanups on tribal lands. More than $7 million has been spent to clean up and close 20 sites and conduct more than 65 UST site assessments and characterizations. EPA’s tribal UST program will receive about $5 million in 2010.

In addition to supporting UST inspections and training, over the past 25 years EPA’s UST Program Office has evolved to include:

- Joint compliance inspections with tribal partners

- Compliance assistance for tribes and tribal coalitions

- Tribal employees leading and presenting on current UST technology at national and regional UST Conferences.

- Extensive training that utilizes UST classrooms and field training

Assisting the Tohono O’odham Nation in UST Inspections

The Tohono O’odham Nation Environmental Protection Office assisted EPA with UST inspections at all facilities on tribal lands. The Tohono O’odham Nation works in collaboration with EPA to ensure that all facilities on the reservation are in compliance to protect groundwater.

Federal Credentials Issued to Navajo Nation under Pilot Field Citation Program

In March 2009, U.S. EPA issued Federal Inspector Credentials to two inspectors from the Navajo Nation EPA. This concluded a two-year process with U.S. EPA’s Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance (OECA). This pilot program allows Navajo inspectors with federal credentials to write field citations for deficiencies they find at an underground storage tank (UST) site. According to an authorization agreement and work plan, these inspectors are slated to conduct 42 inspections of UST sites on the Navajo Nation by the end of August 2009. The Nation had completed 80% of the inspections as of August 12.

National Tribal Compliance Assistance Award to Intertribal Council of Arizona

In 2009, U.S. EPA and the Inter-Tribal Council of Arizona (ITCA) launched a new national cooperative agreement that will provide UST compliance assistance and training support in Indian country. ITCA will provide tribal governments and UST facilities in Indian Country with training, compliance assistance, and collaborative opportunities to prevent leaks from USTs. The goals of this agreement are to promote UST compliance in Indian Country and to support tribes in protecting human health and the environment from UST releases.

Region 9 Tribal Leaking Underground Storage Tank Cleanup Program

In 2005, EPA established the nationwide Indian Country Leaking Underground Storage Tank (LUST) cleanup initiative, which aimed to clean up as many of these sites as possible using federal funding. The Pacific Southwest Region has emerged as a national leader in this project. To date, EPA and tribes in the region have cleaned up 21 leaking sites using federal funding, and initiated investigations at over 120 abandoned and leaking UST sites using combined federal and private funding. Tanks at more than 125 sites have been removed and the sites closed out. EPA worked with 12 tribal governments in the region on this project.

In addition to the federal trust fund, EPA actively works with both tribal and private responsible parties in an effort to complete cleanups using their own funding. When this effort began five years ago, there were close to 275 problem sites on tribal lands in the region. Now, there are just 150 sites. Over the next three years, EPA expects to reduce that number by about 50%.

Superfund Work in Partnership with Tribes to Clean Up and Redevelop Contaminated Lands

The Superfund Program was designed to address abandoned and contaminated hazardous wastes sites that cannot be addressed by other environmental laws. In the 29 year history of the Superfund program, Region 9 has worked with more than 20 tribes to support tribal programs, clean up contaminated sites, prepare for and respond to emergencies, and return contaminated properties to productive use. As a result, we have cleaned up more than one million cubic yards of contaminated soil, cleaned up or replaced 50 contaminated homes, and restored or protected more than 750 acres of tribal land.

The Early Days – Celtor Chemical Works

One of the first Superfund sites cleaned up in Region 9 was the Celtor Chemical Works site, located on the Hoopa Valley Indian Reservation. This former ore concentrating facility was abandoned by the Celtor Chemical Corporation in 1962, leaving behind mine tailings that caused acidic surface water runoff and contaminated the soil with toxic metals. The Trinity River, a valuable fishery for the tribe, flows through the center of the reservation and near the site. Between 1983 and 1987, EPA removed more than 2,600 cubic yards of contaminated soil, diverted springs that threatened to spread contamination to the river, and backfilled, contoured and re-vegetated the land. In 2006, EPA formally certified the entire site for unrestricted reuse.

Working with Tribal Communities to Prepare for Emergencies

The 1986 amendments to the Superfund law established new requirements for emergency planning and community right to know. To help tribes comply with these requirements, EPA awarded emergency planning grants to the Hopi Tribe to establish a Hopi Emergency Services Office, and to the Trinidad Rancheria to update its Emergency Response Plan and to cooperate with six tribes in northwest California on emergency planning and response. EPA also sponsored training for 10 Arizona tribes to oversee underground fuel tank and hazardous substance cleanups. This program enabled the Gila River Indian Community, the Navajo Nation, the Tohono O’odham Nation and the Hopi Tribe to develop their own Tribal Emergency Response Commissions to address human health and environmental threats on reservation land. Gila River Indian Community was the first tribe in Region 9 to develop a full Emergency Planning & Community Right-to-Know Ordinance.

Partners in Emergency Response

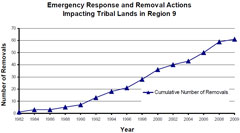

EPA’s Emergency Response Program has a long history of working with tribes to respond to emergencies and clean up sites that threaten human health and the environment. Since 1982, EPA has conducted 61 emergency response or removal actions that affected tribal lands. When soil contaminated with the pesti-cide toxaphene was discovered on Gila River Indian Community land in late 1998, EPA removed approximately 3,400 cubic yards of contaminated soils. After consultation with the tribal community and other stakeholders, EPA built four treatment trenches in which microbes were used to treat contaminated soils placed in innovative plastic liners resembling burritos, creating “The Burrito Project.”

In 2008, EPA’s Superfund program removed 1,400 tons of contaminated ash, 400 pounds of cement pipes containing asbestos, 1,600 pounds of waste oil and sludge, and 100 cubic yards of discarded wooden grape stakes treated with toxic chromated copper arsenate (CCA) at the 25-acre Auclair Dump on the Torres Martinez Reservation.

Superfund Works with Tribes to Clean Up Mines

From 1944 to 1986, nearly four million tons of uranium ore were extracted from Navajo Nation lands in Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. Much work has been done to close and restore the mines, but a legacy of uranium contamination remains from more than 500 abandoned uranium mines, homes built with contaminated waste rock from the mines, and contaminated water wells. Since October 2007, EPA has demolished 27 contaminated homes and other structures, cleaned up 10 residential yards, and rebuilt new structures. In 2009, EPA ordered General Electric to clean up nearly 100,000 cubic yards of contaminated soil at the highestpriority mine, the Northeast Churchrock Mine. EPA and the Navajo Nation are working together toward the goal of protecting human health and the environment in this iconic area of the American West.

At the Cyprus Tohono Mine, a copper mine on the Tohono O’odham Nation, extensive mine waste remained at the site and groundwater was contaminated with uranium. In 2008, EPA oversaw a nearly $50 million cleanup that involved moving approximately one million cubic yards of mine waste into a new lined repository. The remediation will prevent contamination of the groundwater aquifer.

The Yerington Mine site is a 3,400-acre abandoned open-pit copper mine, located about 2-1/2 miles south of the Yerington Paiute Reservation. The site has acid mine drainage, along with groundwater and soil contaminated with heavy metals and radionuclides, raising concerns in the nearby community of Yerington, the Yerington Paiute Tribe, and the Walker River Paiute Tribe. EPA completed emergency removal actions to remove transformers filled with PCBs, cap approximately 100 acres to prevent airborne dust, build a new 4-acre evaporation pond, and reline and remove several fluid collection ponds at a total cost of $1.6 million.

Considering Cultural Issues During Cleanups

In 1998, EPA Region 9 and the Washoe Tribe of California and Nevada hosted the first Tribal Risk Assessment Conference in Las Vegas, Nevada. This venue provided the opportunity for approximately 70 different tribal representatives to come together from across the country to discuss how risk assessment should be applied to tribal and cultural resources. EPA has since worked with Washoe tribal members who live adjacent to the Leviathan Mine Superfund site to assess the risks associated with tribal subsistence practices such as harvesting wild plants for medicinal and food purposes, hunting, and fishing. Because traditional ways of living are so closely linked to the ecosystem, EPA and the tribe are working to identify critical plant and animal species that can be used to help determine exposures and ultimately to calculate the risk. EPA’s 2001 enforcement action resulted in the mining company paying for a pristine 480-acre conservation area that is now managed by the Washoe Tribe and the Nature Conservancy.

The 150-acre Sulphur Bank Mercury Mine, next to Clear Lake and the Elem Indian Colony, is a Super fund site that was once one of California’s largest producers of mercury. Removal of contaminated soil found in residential yards and roads at the Elem Indian Colony required careful planning with tribal members and consideration of sensitive cultural resources. EPA consulted with tribal leaders and was assisted during the removal action by tribal cultural monitors and an archaeologist. As part of this removal action, EPA provided temporary housing for 17 families and built new homes, roads, sidewalks, and water systems. Nearly one-third of the construction crew were tribal members. EPA is currently using American Recovery and Reinvestment Act funding to conduct further cleanup actions.

Revitalizing Contaminated Tribal Lands Through The Brownfields Program

Since 1996, 16 Brownfields grants for assessment and cleanup of contaminated lands have been awarded to tribes in the Pacific Southwest. The Navajo Nation was the first tribe in the region to receive an assessment pilot grant in 1996. In 2001, the Gila River Indian Community was one of two federally-recognized tribes selected as a Brownfields Showcase Community. This award leveraged resources from other federal agencies to address Brownfields sites and support redevelopment.

More recently, under a Brownfields Revolving Loan Fund grant from EPA to the Nevada Division of Environmental Protection, the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony received a nearly $1 million loan to clean up a contaminated industrial site in downtown Reno. This is the first Brownfields loan made to a tribe in the Pacific Southwest Region. In 2008, the tribe excavated and disposed of contaminated soil from the site as part of the cleanup. The site will house a major retail store. Revenues will help repay bonds that funded construction of the new Reno-Sparks Indian Colony Health Center, which serves 9,000 Native Americans in the area. Revenues from the retail development at the Brownfields site will also fund other local services.

In 2009, the Cher-Ae Heights Indian Community of the Trinidad Rancheria near Trinidad, California was awarded a $200,000 cleanup grant under the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act to help remove and dispose of pilings and decking from an old pier that had been treated with toxic creosote.

Brownfields Tribal Response Program Development Grants

In 2003, EPA provided grants to the Navajo Nation, Gila River Indian Community (GRIC), and Tohono O’odham Nation to establish and enhance their Brownfields cleanup and response programs. The Navajo Nation used this funding to develop its own Superfund legislation that gives the tribe authority to conduct and oversee cleanups on Navajo land. GRIC developed its Solid Waste Ordinance and enhanced its Voluntary Cleanup Program. In recent years, EPA has also awarded brownfields tribal reponse program grants to the Yurok Tribe, Salt River Maricopa Indian Community, Hoopa Valley Tribe, and the Rincon Band of Luiseno Indians.

| Pacific Southwest NewsroomPacific Southwest Programs | Grants & FundingUS-Mexico Border | Media Center Careers | About EPA Region 9 (Pacific Southwest)A-Z Index |