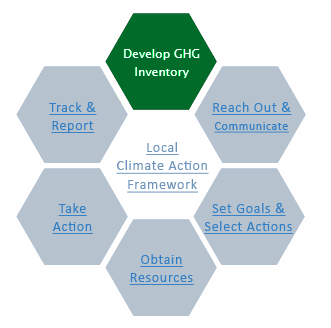

Develop Greenhouse Gas Inventory

There are many metrics related to climate, energy, and sustainability, such as energy use, criteria air pollutants, vehicle miles traveled, and waste generation. This phase focuses on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions inventories, an important metric for most broad climate, energy, and sustainability projects and programs.

Developing GHG inventories can help local entities understand ongoing activities and major sources of emissions; identify areas to focus activities; establish and track progress toward goals; refine or improve existing projects; build and maintain support for programs; compare results with other programs; or facilitate decision-making about future policies or goals.

This phase will walk you through the steps to establish a GHG inventory, including establishing a baseline inventory. You can follow similar approaches for other important metrics related to energy and waste management. Visit the Track & Report phase to find resources for compiling other types of baselines.

The steps in this phase are divided into two different approaches:

- The local government operations approach is for entities that want to understand the GHG emissions of only government facilities and operations (e.g., government buildings and other facilities, streetlights and traffic signals, vehicle fleet). This may be appropriate for government entities interested in promoting green government operations and reducing emissions under their operational control.

- The community-wide approach is for entities that want to understand the GHG emissions of their community as a whole, which can include local government operations. This approach may be more appropriate for entities who want to implement projects to engage the community or adopt a policy to affect change in the community.

Under either approach, local governments may consider partnering with other communities in their region. For local government operations inventories, entities can partner to provide mutual technical assistance and share resources, lessons learned, or best practices (as was done in Central New York). For community inventories, entities can partner to estimate regional GHG emissions. This option can be valuable for small communities that may not have the capacity or resources to conduct inventories independently or that may want to collaborate with other communities on the resulting emissions reduction activities.

Key Steps

For entities that are focused on projects related to government facilities and operations

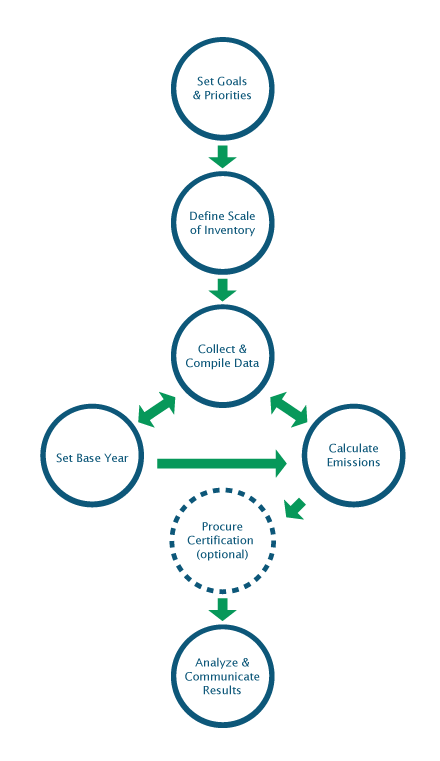

The exact process for developing a greenhouse gas (GHG) inventory for a local government will vary by entity. The guidance presented here outlines several key steps that are likely to be part of any inventory process. The steps are not necessarily intended to be pursued in linear order, and may require multiple iterations, as shown in the diagram. For example, data collection will occur over time and can influence decisions about other components of the inventory.

The industry standard for local government operations GHG inventories is the Local Government Operations Protocol (LGOP)Exit, developed in partnership by the California Air Resources Board, the California Climate Action Registry, ICLEI-Local Governments for Sustainability, and The Climate Registry. The LGOP provides guidance on calculation methodologies, emission factors, and other aspects of inventory development. The guidance here supplements the LGOP, summarizing key steps, lessons learned, and best practices for calculating local government operations GHG emissions.

- Step 1: Set Goals and Priorities

Before you think about the specifics of your local government operations inventory, clearly articulate why you are creating a GHG inventory and how it will be used. Is it to comply with a regulation? Will it inform the development of a climate action plan? Will it provide a baseline from which to monitor progress? Will it enable you to join a GHG registry? Will it be used to inform residents or employees? Having a clear understanding of your goals will inform your decisions throughout the process.

If your goal is...

- To create a comprehensive, comparable inventory: Follow the LGOPExit and include emissions from all inventory sources. The protocol offers many ways to estimate emissions for many (though not all) sources even in the absence of all data.

- To maximize limited resources, or make the most of a partial inventory: Consider doing a partial inventory based on the largest sources (likely building energy use and transportation), or the sources most relevant for your planned actions. You can always add other sources to your inventory over time if more resources become available.

At this point in the process, think about the timeline and level of effort required to complete your GHG inventory. These will vary based on government size and what information is readily available. Consider whether it makes sense for you to do the inventory in-house, work with a local university, or hire a consultant. Also consider how the inventory will be updated, including who will update it and how often.

- Step 2: Define Scale of Inventory

When deciding exactly which departments, activities, and operations to include in your local government operations GHG inventory, consider your goals for the inventory, as well as what falls under your jurisdiction, which sources you want to include, and how you want to organize your inventory. These considerations will help you to develop an estimate that includes all important emissions and avoids double counting.

Set Organizational Boundaries: What Falls Under Your Jurisdiction?

Setting organizational boundaries is an important first step in creating a GHG inventory. In other words, clearly define which facilities and operations fall within your entity’s jurisdiction. While this may seem like a straightforward step, there are multiple ways to define jurisdictional boundaries. The two primary options for defining a jurisdiction are:- Operational control: Under this approach, local governments account for the departments, activities, and operations over which they have “operational control,” or the authority to introduce and implement operating policies. This is the recommended approach in the LGOPExit and the most common way for local governments to set boundaries.

- Financial control: Under this approach, local governments account for the operations over which they have “financial control,” or the operations that are fully consolidated in financial accounts. This approach is consistent with international financial accounting standards.

Determine Which Sources to Include

Next, decide exactly which emission sources to include in your inventory.The LGOP recommends including several “required” emissions sources in GHG inventories to ensure that they are comprehensive and comparable between communities. Consider which areas you may want to target for reductions in deciding whether to include each source, including the “optional” ones. Including “optional” emissions sources provides a more comprehensive image of your local government’s environmental impacts and areas to target with sustainability projects.

LGOP “Required” Emissions Sources

- Fuel combustion and electricity use in facilities (including public buildings, wastewater treatment plants, water pumping stations, and others)

- Electricity use for streetlights, traffic signals, and other public lighting

- Mobile fuel combustion in vehicle fleet and transit fleet

- Solid waste facilities

- Wastewater treatment facilities

LGOP “Optional” Emissions Sources

- Purchased goods and services

- Waste generation

- Electrical power distribution

- Employee commutes

- Employee business travel

- Fugitive refrigerants

- Other Scope 3 sources

Thinking through how your inventory may be organized can be a helpful way to decide which sources to include. Options for organizing your inventory include categorization by scope (see Important Terminology), sector, department, or facility. Sectoral and scope categorization are recommended in the LGOP.

Important Terminology

Direct vs. Indirect EmissionsLocal government operations GHG emissions can be categorized as direct or indirect.

- Direct emissions in government operations inventories are from sources that are located within the local government’s organizational boundaries and that the government owns or controls (e.g., emissions from a municipally owned landfill).

- Indirect emissions occur because of the local government’s actions, but at sources outside the local government’s operational control (e.g., emissions from municipal waste sent to a privately owned landfill).

Scopes

The LGOP uses “scopes” to categorize emissions based on their source. Three scopes together provide a comprehensive account of GHG emissions:- Scope 1: All direct GHG emissions (e.g., emissions from heating oil use in city buildings, gasoline consumption in city vehicles, city-owned wastewater treatment plants).

- Scope 2: Indirect GHG emissions resulting from electricity use. Scope 2 may also encompass emissions from purchased heating, cooling, or steam.

- Scope 3: All other indirect emissions (e.g., emissions resulting from the extraction and production of purchased materials and fuels, contracted solid waste disposal or wastewater treatment, employee commuting and business travel, outsourced activities).

Scopes historically have been used in community inventories as well, although with mixed results. The ICLEI U.S. Community ProtocolExit recommends a different way of categorizing emissions.

Sectors

The LGOP identifies the following local government sectors, which can also be used to categorize emissions: buildings and other facilities, streetlights and traffic signals, water delivery facilities, port facilities, airport facilities, vehicle fleet, transit fleet, power generation facilities, solid waste facilities, wastewater facilities, and other process and fugitive emissions.Activity Data

Defined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) as “data on the magnitude of human activity resulting in emissions or removals taking place during a given period of time,” activity data are the primary pieces of information needed to calculate a GHG inventory. Examples of activity data include the amount of electricity used or vehicle miles traveled in a calendar year.Emission Factor

An emission factor defines the quantity of emissions per unit of fuel or activity. Emissions are calculated by multiplying activity data by the emission factor. For example, emissions from fuel oil combustion are calculated by multiplying gallons of fuel oil used (the activity data) by emissions per gallon of oil (the emission factor). Default emission factors are readily available for many activities; some can be found in the LGOPExit. Keep in mind that emission factors differ for electricity in different parts of the country and for different kinds of fuel oil or natural gas.Carbon Dioxide Equivalents

GHG emissions can be expressed either in physical units (such as grams, tonnes, etc.) of each individual greenhouse gas or in terms of carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2e). A CO2e measurement is derived by multiplying the physical units of the gas by the gas’s global warming potential (GWP). For example, grams of methane (CH4) can be converted to grams of CO2e by multiplying by 25, methane’s GWP.* Metric tons of CO2e is a standard unit for reporting GHG emissions. Conversion factors and GWPs can be found in the LGOPExit.* Note that GWPs can change as science advances. The current GWP for methane used in the U.S. Greenhouse Gas Inventory is 25.

- Step 3: Collect and Compile Data

Make a checklist of your data needs based on the sources you have decided to include, and begin collecting data on those sources. When you conduct your first, baseline inventory, collect data for all the potential base years that are readily available. In Step 4, you will set a base year, but it is often easier to collect data for multiple years at once than to go back to get data for additional years if your needs change (e.g., if certain data are not available for your desired base year).

Keep in mind that data collection can be the most time-intensive step of the inventory process, and it may continue as you begin calculating your emissions.

Start by reaching out to facility managers, utility representatives, and other individuals who may have data, and get a sense of what is and what is not available to you. Identify whether you need to make any institutional arrangements in advance to facilitate data collection. For example, utilities may have specific procedures for requesting data that may require advanced notice. Establishing a Memorandum of Understanding may be an appropriate mechanism to facilitate data-sharing between organizations, if needed.

Tips for data collection:

- Have a single person in charge of the inventory, an “inventory compiler,” who collects data from other entities, such as from a facilities energy lead or a wastewater treatment lead. This individual could not only keep track of the different components, but also help build capacity in the organization by becoming an inventory and emissions expert.

- Minimize the burden of the data request and make it easier for someone to give you the information you need. It can be helpful to provide your data provider with a template to populate (such as a spreadsheet with labeled rows and columns) to help him or her understand exactly what you are looking for and how the data will be used. However, be prepared to take data in whatever form your provider has readily available, for whatever timeframe is available, and then adapt it to your needs.

- Keep track of all units and follow up if the units are not clear in a dataset.

- Keep all data received in an organized manner and carefully document all data sources (including points of contact for collecting the data). This will make it easier for you or others to collect updated data in the future to measure your progress.

- Document the emission factors and GWPs used along with the data. Having these conversion factors readily available helps later when you are reviewing the data and making comparisons.

- Consider what data may be helpful in the future. Try collecting related data if they are readily available, even if you are not sure yet how they may be used.

The following table lists data that are commonly needed for inventories, along with corresponding possible sources of those data. This list is not comprehensive; it is intended to offer only a few common examples

Data Commonly Needed Possible Data Source Facilities - Electricity use

- Fuel use, by fuel type (e.g., natural gas, heating oil, kerosene, propane, coal)

- Accounts payable

- Facility managers

- Local government departmental records

- Public works department

- Utility representatives

- Fuel vendor

- EPA's ENERGY STAR Portfolio Manager

- Electricity emission factors

- EPA’s eGRID (see individual power plant factors in “data files” and regional factors in the “subregion GHG output emission rates” file)

- Natural gas emission factors

- Fuel emission factors, by fuel type

Transportation - Vehicle fuel use, by fuel type

- Vehicle miles traveled

- Accounts payable

- Local government departmental records

- Fleet manager

- Fuel vendors

- Mileage reimbursement records

- Vehicle fuel emission factors, by fuel type

Solid Waste For emissions from city landfills (Scope 1):

- Amount of waste in city landfills

- Composition of waste in city landfills

- Landfill gas collected at city landfills

- Fraction of methane in collected landfill gas

- Landfill gas collection area

For emissions from city landfills (Scope 1):

- Landfill manager/department

- Default waste composition from the state or EPA’s annual report, Advancing Sustainable Materials Management: Facts and Figures

- EPA’s Landfill Methane Outreach Program

For emissions from city-generated waste (Scope 3):

- Amount of waste generated

- Composition of waste generated

For emissions from city-generated waste (Scope 3):

- Waste audit

- Waste hauling company

- Default waste composition from the state or EPA’s annual report, Advancing Sustainable Materials Management: Facts and Figures

Wastewater - Wastewater treatment process details (e.g., aerobic, anaerobic, nitrification, denitrification, biogas collected, system Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD5) load)

- Population served by septic systems

- Wastewater treatment manager/department

- Step 4: Set Base Year

When choosing a base year, consider whether (1) data for that year are available; (2) the year represents a “typical” year for your locality (e.g., no unusual weather or economic conditions); and (3) the base year is coordinated to the extent possible with any goals or commitments your local government may have established (e.g., to reduce emissions by a certain percentage in a specific year, to align with other government programs, to comply with external requirements).

Your inventory base year provides a benchmark against which you can compare future emissions. Of course, inventories can also be conducted (or simply updated) regularly, in order to track progress.

GHG inventories typically describe emissions over the course of a calendar year for ease of data collection and comparison. Datasets that are available only for fiscal years or other periods can be converted to calendar years.

- Step 5: Calculate Emissions

With data collected and a clear vision for which emissions to include, calculate emissions for each of the sources identified in Step 2 by plugging your data and emission factors into the appropriate equations. Several resources are available to help you do these calculations, including protocols that suggest methodologies or equations to use and tools that complete the calculations for you after you enter your data.

For each source within your inventory, choose a methodology for calculating emissions. The primary protocol for local government operations inventories is the LGOPExit, which provides step-by-step instructions and equations for calculating GHG emissions. The LGOP also provides default emission factors and alternate methodologies to choose from based on data availability. The following tips can facilitate the calculation process:

- Decide whether you want to calculate your emissions using a pre-built tool or using your own spreadsheet. Available tools include:

- EPA’s Local GHG Inventory Tool: An EPA tool with two modules. The Government Operations Module implements the LGOP for local government operations GHG inventories.

- ICLEI’s ClearPathExit: An ICLEI GHG inventory and emissions reduction calculator that replaces ICLEI’s Clean Air and Climate Protection software.

- EPA’s ENERGY STAR Portfolio Manager: An EPA tool that estimates GHG emissions for individual buildings based on energy and water use, and allows users to compare their buildings’ performance to similar buildings.

- EPA’s Center for Corporate Climate Leadership Simplified GHG Emissions Calculator: An EPA tool designed to help small businesses estimate and inventory their annual GHG emissions.

- Tools from your state environmental or energy agency.

- Work through your inventory sector-by-sector. For each sector (buildings, streetlights, water delivery, vehicle fleet, power generation, wastewater, solid waste, etc.), try to find the most detailed activity data available and the most locally relevant emission factors. Possible sources of emission factors beyond the LGOP include:

- EPA’s eGRID: Electricity use emission factors by region and power plant

- EPA’s Power Profiler: Electricity use emission factors by ZIP code

- EPA’s Waste Reduction Model (WARM): Solid waste emission factors for different material types

- Carnegie Mellon University’s Economic Input-Output Life Cycle Assessment (EIO-LCA)Exit: Emission factors to estimate the GHG and energy impacts of purchased goods and services

- If “ideal” data or emission factors are not available, think about alternate methods you can use to estimate emissions for each sector. For example, if local or state emission factors are not available, use national factors as proxies. If data are not available for the right year, use data from the closest year available and adjust by some factor (e.g., using population growth). The LGOPExit provides several methodologies. If the LGOP does not provide methodologies that meet your needs, other protocols can provide ideas, such as the following from the Greenhouse Gas Protocol:

- Match methodology to goals and available resources. The best methodology to use will depend on the goals for the inventory, as well as the amount of time, resources, and data available. Detailed, bottom-up approaches may not be necessary in all cases, such as if your local government needs just a high-level, “order of magnitude” estimate of baseline conditions.

- Review other GHG inventories. Review inventories from local governments, your state, and even the national GHG Inventory for inspiration about data sources and emission factors.

- Document all assumptions and data sources.

- Use other GHG inventories to help you check your results. Compare your estimated emissions to those of a similarly sized local government. Check whether your estimates are in the same order of magnitude. It may be most useful to compare estimates on a line-item basis (e.g., for only building energy use), as total emissions may be different due to a variety of factors, including community size, type of electric utility, and climate, as well as different sources included. Examples of local GHG inventories are available on the Local Examples page.

- If you get stuck, contact us.

Helpful Tip: How you choose to calculate your emissions can evolve throughout the inventory process, as more data become available or as your needs evolve. It is okay to revise your quantification approach throughout the process.

Helpful Tip: How you choose to calculate your emissions can evolve throughout the inventory process, as more data become available or as your needs evolve. It is okay to revise your quantification approach throughout the process.Generally, approaches are either:

- Bottom-up: Based on local data about activities in your government (e.g., emissions = natural gas use (derived from utility bills) × utility-specific natural gas emission factor). Bottom-up approaches are preferred for local government inventories, if data are available.

- Top-down: Based on data compiled by a state, regional, or federal agency or office providing information for specific geographic areas (e.g., the Energy Information Administration (EIA) State Energy Data system). Local governments can use this information as part of a proxy methodology to estimate emissions if activity data are not available. For example, if a local government did not know the amount of natural gas used to heat buildings, it could use a national or state average for natural gas use per square foot (or similar) and the building’s size to estimate its natural gas use.

Note: You cannot use a top-down approach to measure your progress toward reducing GHG emissions. To measure whether sustainability efforts are working, you must use actual measurements of energy use and other metrics in a bottom-up analysis.

- Decide whether you want to calculate your emissions using a pre-built tool or using your own spreadsheet. Available tools include:

- Step 6: Procure Certification (optional)

Depending on your situation, you may want to consider enlisting a third-party review and certification of the methods and underlying data to ensure that the inventory is of high quality, transparent, accurate, complete, consistent, and comparable. Certification may also be required for participation in some greenhouse gas registries.

Examples of GHG inventory certifications include:

- California Climate Action Registry General Verification ProtocolExit

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 14061-1 (inventory)Exit and 14064-3 (verification)Exit Standards

- Step 7: Analyze and Communicate Results

Analyze Results

Valuable lessons can be gained from your GHG inventory. Draw “big picture” lessons from the results to understand the driving forces behind emissions, answering questions like:- What are the largest sources of emissions in our local government’s operations?

- Why are the emissions so high? Is it a result of high activity data, high emission factors, or both?

- How do our operational emissions in a sector compare to those of other, similar governments? If they are noticeably higher or lower, why?

- What are the drivers of our operational emissions?

- What are our emissions per capita? Per employee? Per heating degree-day? Per cooling degree-day?

Degree-Days

A degree-day is a unit of measurement that compares the outdoor temperature in a time period to a standard of 65°F. Degree-days are useful for comparing energy use across periods with different weather conditions. In GHG inventories, they can help determine how much of a year-to-year change in emissions was caused by weather instead of other factors. Hot days are measured in cooling degree-days and cold days are measured in heating degree-days. Additional information is available from the U.S. Energy Information AdministrationExit. Use the lessons learned from your inventory to inform emissions and energy use reduction efforts. See the Set Goals & Select Actions and Promote Green Government Operations phases for more information.Continue to monitor emissions over the course of your project (e.g., by regularly tracking key data such as energy use or by conducting an inventory every year or two) to evaluate the progress and success of your efforts. It is easier to update an inventory regularly than to collect data for several years at once to see trends. Visit the Track & Report phase for more information.

Communicate Results

Communicate the results of your inventory to community members and to others within the local government. Consider telling a story about the government’s energy use and emissions, rather than simply reporting the numbers. For example, you may explain that the local government has relatively low electricity use compared to other, similarly sized governments, but it gets electricity from a fuel source with higher carbon intensity. In subsequent years, you can tell the story about what is driving trends in your emissions (e.g., energy efficiency efforts, economic growth, population change, weather). Look at other inventory reports for inspiration on format and content.EPA’s GHG Equivalencies Calculator is a resource that can help translate GHG emission amounts into terms that are more easily understood. For example, the calculator translates emissions in metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) into more relatable terms, like “annual emissions from X number of cars.”

You may also consider reporting your emissions through the Carbon Disclosure Project cities programExit.

See the Reach Out & Communicate phase for more information on communicating inventory results to key stakeholders and the public.

For entities that are focused on projects related to affecting change in the community

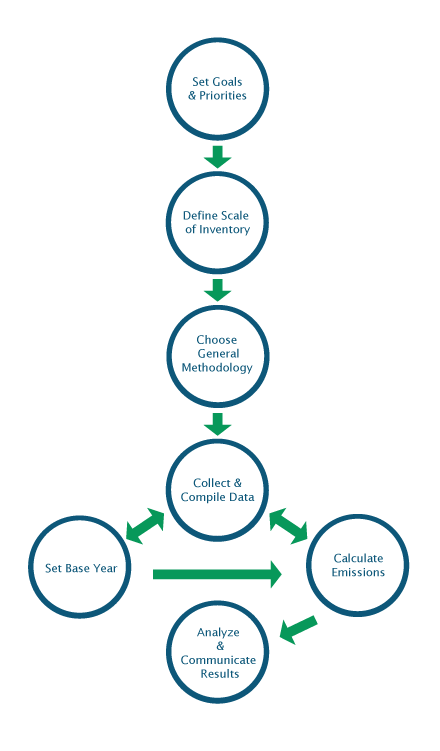

The exact process for developing a community-wide greenhouse gas (GHG) inventory will vary by entity. This guidance outlines several key steps that are likely to be part of any inventory process. The steps are not necessarily intended to be pursued in linear order, and they may require multiple iterations, as shown in the diagram.

The ICLEI U.S. Community Protocol for Accounting and Reporting of Greenhouse Gas Emissions (ICLEI U.S. Community Protocol)Exit provides guidance on calculation methodologies, emission factors, and other aspects of community-wide inventory development. The guidance presented here supplements the ICLEI U.S. Community Protocol, summarizing key steps, lessons learned, and best practices for estimating community-wide emissions.

- Step 1: Set Goals and Priorities

Before you think about the specifics, clearly articulate your goals and priorities for the inventory. What is it you want to know? What stories do you want to tell your community about its GHG emissions? Keep these goals in mind as you decide which emissions sources and activities to include (see Step 2).

For example, if your goal is to reach out to community members to reduce their environmental impact, you might want to focus on emissions from residential energy use, community member travel, and residential waste generation and disposal. However, if your goal is to identify programs to maximize emissions reductions, you might want to focus on emissions from the sources and activities that typically generate the most emissions and that your community can reasonably control, such as emissions from building energy use or from purchased materials.

You might also decide to use a consumption-based accounting approach to communicate to residents how their direct activities contribute to emissions or to understand how households with different spending patterns contribute to emissions, the emissions intensities (emissions per dollar) of different forms of consumption, and how emissions might change if consumption were to shift.

Refer to the reporting frameworks in the ICLEI U.S. Community ProtocolExit for more story ideas.

As you set goals and priorities, also think about the timeline and level of effort required to complete your GHG inventory. These will vary based on community size and available information. Consider whether it makes the most sense to do the inventory in-house, work with a local university, or hire a consultant.

If your organization does not have the time or resources to complete a thorough inventory, consider doing a partial inventory based on your goals and priorities. This way, you have a baseline to work from that will be relevant to emissions and energy reduction measures, even if it is not a complete inventory.

- Step 2: Define Scale of Inventory

Next, define the scale of the inventory, including the community boundary and which sources and activities to include. These considerations will help you to develop an estimate that includes all important emissions and avoids double counting.

Define Community Boundary

Though likely straightforward, it is important to clearly define the jurisdictional boundary of your inventory. The boundary of a community-wide base inventory is typically determined by the geographical boundary of the community. However, you might need to decide whether to include or exclude incorporated areas (e.g., a village within a town).Determine Which Sources and Activities to Include

Consider and identify the various GHG emission sources and activities to include in your inventory. Consider the following questions as you identify what to include.What are sources and activities, and why distinguish between them?

The ICLEI U.S. Community ProtocolExit specifically distinguishes between the sources of emissions and activities resulting in emissions. These two categories overlap, and you do not need to decide to include only sources or only activities. However, drawing a distinction between types of emissions can help you to better understand, organize, and report emissions associated with your community.-

The sources emissions are any physical processes at locations inside the jurisdictional boundary that directly produce GHGs. They can be thought of as “stack pipe” or “tail pipe” emissions and result in GHGs that actually enter the atmosphere within the physical boundaries of your community. Examples include burning coal to generate electricity at a power plant, the use of fuel oil in residential homes, vehicles driving within the community, industrial facilities, solid waste disposal facilities, wastewater treatment facilities, and domesticated livestock production within in the community.

-

Activities refer to any uses of energy, materials, or services by members of the community that result in emissions, regardless of where the emissions occur. Examples include electricity use, home heating and cooling, air travel by members of the community, solid waste generation, water use, and the purchase and use of materials. These activities are under the direct control or influence of residents and businesses within the community and may result in emissions originating either inside or outside the community’s borders. Activities that generate emissions originating within the community boundary (e.g., driving a gas-powered vehicle within the community, heating a home with oil) can be considered both a source and an activity

Distinguishing between sources and activities can help communities identify different types of measures to reduce emissions. In addition, it can help communities avoid double counting emissions. Emissions associated with either sources or activities alone can generally be summed, but carefully examine emissions from sources and activities before summing them to prevent double counting them within the total.

Sources vs. Activities: Materials Management Example

Methane emissions from landfilled organic waste can be accounted for in two ways:- As a source: Landfills located within community boundaries are considered emissions sources because the landfills physically emit greenhouse gases within the community boundary. These emissions result from all organic waste in the landfill, regardless of where the waste was generated.

- As an activity: Waste generated within the community, regardless of where it is landfilled, is considered an activity in the community that generates emissions.

Both methods of accounting could be beneficial for developing emissions reduction strategies. Understanding emissions from the in-boundary source may highlight opportunities to reduce emissions through changes in landfill management, while accounting for emissions from the waste generation activity might help to identify opportunities to reduce emissions through waste reduction programs. However, be careful about adding together emissions from the landfill and emissions from waste generation: if waste generated by the community is also landfilled in the community landfill, summing the activity and source emissions would constitute double counting.

Local government operations inventories categorize emissions in a different way than community inventories. View Step 2 for additional information.

What are the possible sources and activities?

The ICLEI U.S. Community ProtocolExit recommends several sources and activities as “required” in GHG inventories because communities typically have influence over these emissions, data are reasonably available, these emissions tend to be significant, and they are common in the United States. The following five basic emissions-generating sources and activities are considered “required”:- Electricity use in the community (activity)

- Fuel use in residential and commercial facilities (source and activity)

- On-road passenger and freight motor vehicle travel (source and activity)

- Energy used to treat and distribute water and wastewater used in the community (activity and sometimes source)

- Generation of solid waste by the community (activity)

Including other “optional” sources and activities provides a more comprehensive image of the community’s environmental impacts and areas to target with sustainability projects. Select sources and activities based on the goals of the inventory and other sustainability programs, data availability, and resource availability. See Table 2 of the ICLEI U.S. Community ProtocolExit for a list of other sources and activities. Consider going through this list with your goals in mind and deciding one-by-one whether to include each source and activity.

Important Terminology

Sources vs. Activities

See the description above.Activity Data

Defined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) as “data on the magnitude of human activity resulting in emissions or removals taking place during a given period of time,” activity data are the primary pieces of information needed to calculate a GHG inventory. Examples of activity data include the amount of electricity used or vehicle miles traveled in a calendar yearEmission Factor

An emission factor defines the quantity of emissions per unit of fuel or activity. Emissions are calculated by multiplying activity data by the emission factor. For example, emissions from fuel oil combustion are calculated by multiplying gallons of fuel oil used (the activity data) by emissions per gallon of oil (the emission factor). Default emission factors are readily available for many activities; some can be found in the Local Government Operations Protocol (LGOP)Exit or ICLEI U.S. Community ProtocolExit. Keep in mind that emission factors differ for electricity in different parts of the country and for different kinds of fuel oil.Carbon Dioxide Equivalents

GHG emissions can be expressed either in physical units (such as grams, tonnes, etc.) of each individual greenhouse gas or in terms of carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2e). A CO2e measurement is derived by multiplying the physical units of the gas by the gas’s global warming potential (GWP). For example, grams of methane (CH4) can be converted to grams of CO2e by multiplying by 25, methane’s GWP.* Metric tons of CO2e is a standard unit for reporting GHG emissions. Conversion factors and GWPs can be found in the LGOPExit or ICLEI U.S. Community ProtocolExit.* Note that GWPs can change as science advances. The current GWP for methane used in the U.S. GHG Inventory is 25.

-

- Step 3: Choose General Methodology

The quantification method and year used for the GHG inventory, as well as the sources and activities you choose to include, will depend on what data are available. Before collecting data, it is helpful to determine what general methodology you will use to complete your inventory. Generally, approaches are either:

- Bottom-up: Based on local data about activities in your community (e.g., emissions = natural gas use (derived from utility data) × utility-specific natural gas emission factor).

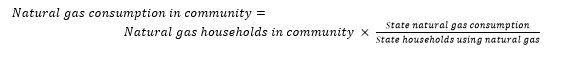

- Top-down: Based on data compiled by a state, regional, or federal agency or office providing information for specific geographic areas. You can use this information as part of a proxy methodology to estimate emissions if activity data are not available. For example, a community could estimate natural gas use in their area based on publicly available information from the EIA and Census Bureau:

- Number of households in community using natural gas (American Community Survey)

- Statewide natural gas use (EIA State Energy Data System)

- Number of households in state using natural gas (EIA Residential Energy Consumption Survey)

- Hybrid: Inventories can use a combination of bottom-up and top-down approaches, based on data availability.

The best approach for a community will depend on the goals for the inventory, time and resources available, and data availability. Detailed, bottom-up approaches may not be necessary in all cases, such as if an entity needs just a high-level, “order of magnitude” estimate of baseline conditions. If you decide to pursue a top-down approach, you may be able to spend less time collecting and compiling data, relying instead on state, regional, or national datasets.

However, note that you cannot use a top-down approach to measure your progress toward reducing GHG emissions. To measure whether sustainability projects are working, you must use actual measurements of energy use and other metrics in a bottom-up approach.

- Step 4: Collect and Compile Data

Make a checklist of your data needs based on the sources and activities you have decided to include, and begin collecting data to calculate emissions in your community. When you are conducting your first, baseline inventory, collect data for all potential base years that are readily available. In Step 5, you will set a base year, but it is often easier to collect data for multiple years at once than it is to go back to get data for additional years if your needs change (e.g., if data are not available for your desired base year).

Keep in mind that data collection can be the most time-intensive step of the inventory process, and and it may continue as you begin calculating your baseline.

Start by reaching out to utility representatives, transportation planners, and other individuals who may have data, and get a sense of what is and is not available to you. Identify whether you need to make any institutional arrangements in advance to facilitate data collection. For example, utilities may have specific procedures for requesting data that may require advanced notice. Establishing a Memorandum of Understanding may be an appropriate mechanism to facilitate data-sharing between organizations, if needed.

Tips for data collection include:

- Have a single person in charge of the inventory, an “inventory compiler,” who collects data from other entities, such as from a facilities energy lead or a wastewater treatment lead. This one person can not only keep track of the different components, but can help build capacity in the organization by becoming an inventory and emissions expert.

- Minimize the burden of the data request and make it easier for someone to give you the information you need. It can be helpful to provide your data provider with a template to populate (such as a spreadsheet with labeled rows and columns) to help him or her understand exactly what you are looking for. However, be prepared to take data in whatever form your provider has readily available, and then adapt it to your needs.

- Keep track of all units and follow up if the units are not clear in a dataset.

- Keep all data received in an organized manner and carefully document all sources of information (including points of contact for collecting the data). This will make it easier for you or others to collect updated data in the future to measure your progress.

- Document the emission factors and GWPs used along with the data. Having these conversion factors readily available helps later when you are reviewing the data and making comparisons.

- Consider what data may be helpful in the future. Try collecting related data if they are readily available, even if you are not sure yet how they may be used.

- Reach out to utilities early. Utilities can be a valuable source of information on community-wide electricity or natural gas use. However, many communities have had difficulty collecting data from utilities because of concerns over data confidentiality or the length of time required to provide the data. To overcome these challenges, reach out to utilities early in the process and rely on any existing relationships. In addition, be prepared to work with data in whatever form the utility is willing to provide. You may also consider coordinating with other communities to streamline data requests.

The following table lists data that are commonly needed for inventories, along with corresponding possible sources of those data. This list is not comprehensive; it is intended to offer only a few common examples.

Data Commonly Needed Possible Data Source General - Population

- Number of households

- U.S. Census Bureau, American Communities Survey

Facilities - Electricity use

- Residential fuel use, by fuel type (e.g., natural gas, heating oil, kerosene, propane, coal)

- Commercial fuel use

- Industrial stationary fuel use

- Utilities

- Fuel vendors

- State-level averages of fuel use per-household

- EPA’s database of GHG emissions from large facilities

- Electricity emission factors

- EPA’s eGRID (see individual power plant factors in “data files” and regional factors in the “subregion GHG output emission rates” file)

- Natural gas emission factors

- Fuel emission factors, by fuel type

Transportation - Vehicle fuel use, by fuel type

- Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT)

- Regional travel demand model

- Metropolitan Planning Organization or state Department of Transportation

- Vehicle fuel emission factors, by fuel type

- Off-road vehicle activity

- EPA’s NONROAD model

- Flight miles into/out of local airports

Solid Waste - Solid waste generated by community

- Composition of waste generated by community

- Solid waste department

- Local landfills

- Municipal hauler

- National, state, or local survey of averages of waste composition or per capita waste generation

Wastewater - Wastewater treatment process details (e.g., aerobic, anaerobic, nitrification, denitrification, biogas collected, system Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD5) load)

- Wastewater treatment manager/department

Industrial Processes - Industrial process emissions

- EPA’s database of GHG emissions from large facilities

- Step 5: Set Base Year

When choosing a base year, consider whether (1) data for that year are available, (2) the year represents a “typical” year for your community (e.g., no unusual weather or economic conditions), and (3) the base year is coordinated to the extent possible with any goals or commitments your community may have established (e.g., to reduce emissions a certain percentage below those in a specific year, to align with other community programs, to comply with external requirements).

Your base year provides a benchmark against which you can compare future emissions. Of course, inventories can also be conducted (or simply updated) regularly, in order to track progress.

GHG inventories typically describe emissions over the course of a calendar year for ease of data collection and comparison. Datasets that are available only for fiscal years or other periods can be converted to calendar years.

- Step 6: Calculate Emissions

With data collected and a clear vision for which emissions to include, calculate emissions for each of the sources and activities identified in Step 2 by plugging in your data and emission factors into the appropriate equations. Several resources are available to help you do these calculations, including protocols that suggest specific methodologies and tools that complete the calculations for you after you enter your data. Ultimately, the methodology you use to calculate GHG emissions for each source or activity will depend on what data are available.

For each emissions source or activity, choose a methodology for calculating emissions. The ICLEI U.S. Community ProtocolExit suggests multiple methodologies to choose from based on data availability, along with step-by-step instructions, emission factors, and equations for calculating GHG emissions. If the ICLEI U.S. Community Protocol does not meet your needs, other protocols can provide ideas, such as the Local Government Operations ProtocolExit or the following from the Greenhouse Gas Protocol:

- Global Protocol for Community-Scale Greenhouse Gas Emission InventoriesExit

- A Corporate Accounting and Reporting StandardExit

- The GHG Protocol for Project AccountingExit

- Corporate Value Chain (Scope 3) Accounting and Reporting StandardExit

The following tips can also facilitate the calculation process:

- Decide whether you want to calculate your emissions using a pre-built tool or your own spreadsheet. Available tools include:

- EPA’s Local GHG Inventory Tool: An EPA tool with two modules. The Community Module facilitates the use of the ICLEI U.S. Community Protocol.

- ICLEI’s ClearPathExit: An ICLEI GHG inventory and emissions reduction calculator that replaces ICLEI’s Clean Air and Climate Protection software.

- EPA’s ENERGY STAR Portfolio Manager: An EPA tool that estimates GHG emissions for individual buildings based on energy and water use.

- Work through your inventory sector-by-sector. For each sector (e.g., built environment, transportation, solid waste, wastewater), try to find the most detailed activity data available and the most locally relevant emission factors. Possible sources of emission factors include:

- EPA’s eGRID: electricity use emission factors by region and power plant

- EPA’s Power Profiler: electricity use emission factors by ZIP code

- EPA’s Waste Reduction Model (WARM): solid waste emission factors for different material types

- Carnegie Mellon University’s Economic Input-Output Life Cycle Assessment (EIO-LCA)Exit: emission factors to estimate the GHG and energy impacts of purchased goods and services

- If “ideal” data or emission factors are not available, think about alternate methods you can use to estimate emissions for each sector. For example, if data on community-wide heating fuel usage are not available, use Census Bureau data on the number of homes using each type of heating fuel and the national average heating fuel consumption per household to estimate your community’s usage. The ICLEI U.S. Community ProtocolExit provides alternate methodologies. In addition, you can check other community inventory reports to see if and how they have overcome data gaps.

- Match methodology to goals and available resources. The best methodology for a community to use will depend on the goals for the inventory, as well as the amount of time, resources, and data available. Detailed, bottom-up approaches may not be necessary in all cases, such as if your community needs just a high-level, “order of magnitude” estimate of baseline conditions.

- Review other GHG inventories. Review inventories from local governments, your state, and even the U.S. GHG Inventory for inspiration about data sources and emission factors.

- Revise your approach, as needed. How you choose to calculate your emissions can evolve throughout the inventory process, as more data become available or as your needs evolve. It is okay to revise your approach throughout the process.

- Document all assumptions and data sources.

- If you get stuck, contact us.

- Step 7: Analyze and Communicate Results

Analyze Results

Valuable lessons can be gained from your GHG inventory. Draw “big picture” lessons from the results to understand the driving forces behind your estimates, answering questions like:- What are the largest sources of emissions in your community? What are the activities in your community that contribute most to greenhouse gas emissions?

- Why are the emissions so high? Is it a result of high activity data, high emission factors, or both?

- How do your community’s emissions in a source or activity compare to those of other, similar communities? If they are noticeably higher or lower, why?

- What are the drivers for energy use and emissions in your community?

- What are emissions per capita? Per employee? Per heating degree-day? Per cooling degree-day?

Degree-Days

A degree-day is a unit of measurement that compares the outdoor temperature in a time period to a standard of 65°F. Degree-days are useful for comparing energy use across periods with different weather conditions. In GHG inventories, they can help determine how much of a year-to-year change in emissions was caused by weather instead of other factors. Hot days are measured in cooling degree-days and cold days are measured in heating degree-days. Additional information is available via the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Use the lessons learned from the baseline estimate to inform emissions and energy use reduction efforts. See the Set Goals & Select Actions phase for more information.Continue to monitor emissions over the course of your project (e.g., by regularly tracking key data such as energy use or conducting an inventory every year or two) to evaluate the progress and success of your efforts. It is easier to update an inventory regularly than to collect data for several years at once to see trends. See the Track & Report phase for more information.

Communicate Results

Communicate the results of your inventory to community members and others. If desired, refer to Section 4 of the ICLEI U.S. Community ProtocolExit for instructions on how to complete a protocol-compliant inventory report and for general recommendations on how to communicate results in clear, transparent, and useful ways that are not misleading.Communities have found it helpful to tell a story about their energy use and emissions, rather than simply reporting the numbers. For example, you may explain that the community has relatively low electricity use compared to other communities, but gets electricity from an electricity source with high emissions intensity. In subsequent years, you can tell the story about what is driving trends in your community’s emissions (e.g., energy efficiency efforts, economic growth, population change, weather). Look at other inventory reports to see what stories other communities have told and how they have visualized that information. Key stories might highlight:

- Areas where the local government has significant influence to make changes

- Activities of interest to the community, regardless of its local government’s influence

- Household-level emissions that might inspire residential behavior change

Refer to the reporting frameworks in the ICLEI U.S. Community ProtocolExit for more story ideas.

EPA’s GHG Equivalencies Calculator is a resource that can help translate GHG emission amounts into terms that are more easily understood. For example, the calculator translates emissions in metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) into more relatable terms, like “annual emissions from X number of cars."

You may also consider reporting your emissions through the Carbon Disclosure Project cities programExit.

See the Reach Out & Communicate phase for more information on communicating inventory results to key stakeholders and the public.

Case Studies

Syracuse, New York: GHG InventoryExit

GHG emissions and energy use inventory for 2002, 2007, and 2010, covering both local government operations and community emissions.

Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC): Regional GHG InventoryExit

Regional GHG inventory allocating emissions across each of the region’s nine counties and 352 municipalities, conducted for 2005 and updated for 2010.

City of Creve Coeur, Missouri: Baseline GHG InventoryExit

The GHG inventory for both local government operations and community emissions in a 16,868-person city, including suggested items to reduce emissions.

King County, Washington: GHG InventoryExit

GHG inventories for 2000, 2003, 2008, and 2010, including government operations and community emissions. Community emissions in 2008 are reported using two different accounting frameworks.

Chicago, Illinois: 2010 Regional GHG InventoryExit

2010 community-wide inventory that includes community and local government operations emissions for the City of Chicago and the surrounding seven-county region.

Tools and Templates

EPA's Local GHG Inventory Tool

An EPA tool with two modules that help users calculate local government operations and community-wide GHG inventories, respectively, by facilitating data collection and compilation, and generating summary reports.

ICLEI's ClearPathExit

A tool that helps users analyze the benefits of emissions reduction measures and track emissions progress over time. ClearPath is free to ICLEI members and a 60-day free trial is available for non-members.

EPA's ENERGY STAR® Portfolio Manager

A tool to measure and track energy use, water use, and GHG emissions in buildings.

EPA's Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program

A website that includes access to EPA’s tool to explore GHG emissions from large facilities around the United States, including by location, process, industry, gas, or facility.

EPA's State Inventory and Projection Tool

An EPA tool designed to help state governments calculate GHG emissions, with 11 source-based modules. Although it’s designed for states, local governments can use the tool by entering local activity data.

Further Reading

Local Government Operations ProtocolExit

Information on how to conduct a GHG inventory for local government operations, including equations and methodologies, default emission factors, and guidance on reporting emissions.

ICLEI U.S. Community Protocol for Accounting and Reporting of Greenhouse Gas EmissionsExit

Guidance on calculating and reporting community-wide GHG emissions, including equations, methodologies, and default emission factors.

EIA State Energy Data SystemExit

National database of energy use, prices, expenditures, and production by state, energy source, and sector with data for every year since 1960.

EPA Webcast: Greenhouse Gas Inventory 101 for Local, Regional, and State Governments

Slides, recordings, and transcripts from a series of webcasts for state and local governments on GHG inventories.

Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks

National GHG inventory report providing background information and estimation methodologies for all U.S. emission sources.

Acknowledgements:

EPA would like to acknowledge David Allaway (Oregon Department of Environmental Quality), Chris Carrick (Central New York Regional Planning and Development Board), Rob Graff (Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission), Alicia Hunt (City of Medford, Massachusetts), and John Richardson (Town of Chapel Hill, North Carolina) for their valuable input and feedback as stakeholder reviewers for this page.