Cazenovia Creek Habitat Restoration and Stewardship Project

Contact: Karen Rodriguez (rodriguez.karen@epa.gov)

This project was completed in 2002.

I. INTRODUCTION

In August 1999, the Erie County Department of Environment and Planning (DEP) was awarded a $69,750.00 grant from the Great Lakes National Program Office (GLNPO) of the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). This funding was provided in order to pursue a project entitled “Cazenovia Creek Habitat Restoration and Stewardship Project” heretofore referred to as “the project.” Erie County contributed $49,610.00 of the total project costs, which were $119,360.00. The goal of the project was to restore habitat in the Buffalo River Watershed, specifically Cazenovia Creek, and to institute a perpetual community-level stewardship resource for its continual protection.

The Erie County Legislature passed the Resolution to implement the project on November 4, 1999. Due to staff turn over, the original completion date of September 30, 2001 was extended, at no-cost, to the USEPA. The grant was officially closed out on May 31, 2002.

Cazenovia Creek was, in part, chosen for this project because it is a main tributary to the Buffalo River of which the lower portion had been identified by the Great Lakes Water Quality Board of the International Joint Commission (IJC) as one of the 43 Areas of Concern (AOC) in the Great Lakes Region. This designation was due to the river’s poor water quality and contaminated sediments. Through previous research it is determined that much of sediment load to the Buffalo River has its source in the upper watershed, along the streambanks of Cazenovia Creek. Sediments originating in Cazenovia Creek transport and deposit contaminants into the Buffalo River.

DEP’s project proposal outlined three key elements in order to meet the goals of habitat restoration and community stewardship. These elements were organized into three phases:

- Phase I: Establish a Project Partnership

- Phase II: Curriculum Development

- Phase III: Program Implementation

Each of these three phases is described in detail in the subsequent sections. The final section of this report is the conclusion, which focuses on accomplishments, as well as lessons learned throughout the project. It is the goal of that last section to reveal factors, ideas, and questions for other entities to consider when pursuing such an initiative.

Phase I

ESTABLISH A PROJECT PARTNERSHIP

The first step was to establish a steering committee, and the first meeting was held in May 2000. Now called the Cazenovia Creek Curriculum Committee (CCCC), it was made up of representatives from Erie County DEP, Erie County Soil and Water Conservation District (SWCD), New York Sea Grant, and teachers from Main Street Elementary (East Aurora), Potters Road Elementary and Winchester Elementary (West Seneca), Holland Central High School (Holland), and The Gow School (South Wales). A teacher from the Amherst School District served as an advisor of the Adopt-A-Stream program. In 2001, three more teachers/classrooms from the Buffalo Public Schools joined the CCCC. A private school, The Park School of Buffalo, also joined in 2002, which brings the total schools to nine.

The following summarizes the activities of the CCCC since May 2000:

- the CCCC met 11 times over two years

- CCCC members participated in two trainings - Aquanauts, and Project WET (Water Education for Teachers)

- Planned, organized and implemented the Cazenovia Creek Lab Day, held March 7, 2001 at Winchester Elementary School

- assisted with the organization of 7 Cazenovia Creek streambank plantings and clean-ups

- conducted 4 watershed tours with students

- laid a framework for curriculum

In November 2001, a new initiative called "Western New York: Connecting To Learn" was established and approximately 30 new program partners began to collaborate on regional environmental education. The Program will connect students from urban, rural, and suburban communities via long distance learning and video conference technology. The steering committee was divided up into three working groups, Organizational Infrastructure, Technology, and Curriculum Development. CCCC members Helen Domske, Dianne Johnson, Gail Hall, Jill Jedlicka, and Joanna Tuk have focused their Cazenovia Creek efforts into participation on the Connecting To Learn Program.

The following summarizes the activities of the C2L Working Groups since November 2001:

- 13 working group or steering committee meetings

- identification of over 60 schools who are eligible to participate

- outline for curriculum for 2002-2003 pilot project

- hosted live media event to launch the program

Phase II

CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT

The main goal of this task, as proposed, was "to develop the desired level of community outreach and support for the restoration project", and to "encourage teachers to use the watershed as an outdoor living laboratory". Stewardship components were established as critical objectives.

The curriculum will be finalized during the summer and fall of 2002. The Connecting To Learn Program will utilize the experiences and lessons learned in the Cazenovia Creek Project to assemble water quality and stewardship curriculum.

The curriculum framework is to include:

- Five key instructional elements

- water quality

- field trips

- cooperative learning

- technology

- team driven/expert learning

- The five core ideas will include

- Community/School Based projects & Environmental Stewardship

- Ecosystem Health

- Watershed Focus/Connecting Local to Global Issues

- Water Quality

- Aquatic Ecology

- Basis for curriculum development by using the following:

- Cazenovia Creek Habitat Restoration and Stewardship Project

- Aquanauts Water Quality testing program

- NYS Angler Cohort Study

- Niagara Falls Aquarium Aquatic Ecology Program

The Connecting To Learn program will offer a "Watershed FX - Futuristic and eXperiential" curriculum that will be project driven. Teachers will be trained in technology and curriculum, but allow for independent implementation of the program into their classrooms.

The curriculum will be localized within the watershed and the participating students will be identified as teams to generate buy-in at the student level. Teachers will be required to take part in a training, and they will get instruction/training, educational materials, support services and contacts with experts. The curriculum will help implement New York State Learning Standards 1,2,4,6 and 7. Teachers and administrators will be accountable and required to apply the project into their local community.

Because of the relationship with project partners and Erie I and Erie II BOCES (Board of Cooperative Educational Services) local schools who participate in the Watershed FX program may be eligible for reimbursement of up to 60-90% of their costs, and in essence the program becomes self-sustaining.

Local Girl Scouts participate in a water education workshop at Earth Day Exposition 2002 at Buffalo State College.

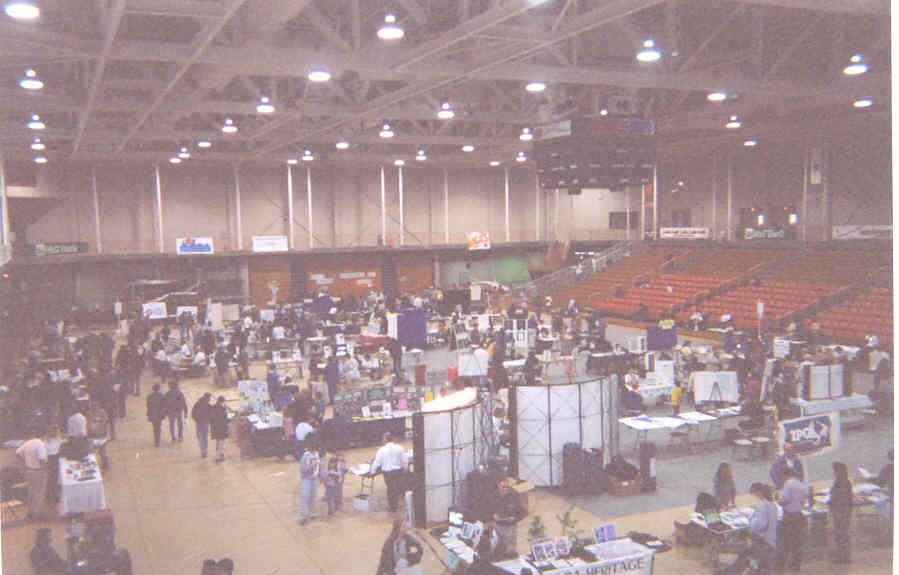

View of the Buffalo State College Sports Arena during Earth Day Expo 2002. It is

estimated that 2,500 people attended the event throughout the day.

"Ronny the Raindrop", the Erie County SWCD mascot, poses in front of several displays at the Earth Day Expo 2002

Phase III: Implementation

The category of "program implementation" consists of everything from teacher and student training, to fieldwork, cooperative learning, etc. The major tasks associated with this phase include the plantings, data collection and sharing, and promotion of environmental stewardship.

- Teacher trainings - summer 2001

- EnviroScape presentations - 8 total

- Aquanauts water quality testing - 6 sites, 8 events

- Cazenovia Creek Lab Days - 2 total, one only for Winchester students

- Watershed tours - 4 total

- Streambank plantings - 5 locations, 7 events

- Publicity and environmental education

- Environmental Events - 5 total (2001 Great Lakes Student Summit, two Earth Day Expos, and 2 Earth Day T-shirt Contests)

- Curriculum development

- Next steps - Connecting To Learn curriculum set to be completed by Fall 2002, implemented into five pilot classrooms in Spring 2003.

Conclusion: Accomplishments and Lessons Learned

Each of the project tasks resulted in many accomplishments and revealed lessons that the DEP can be applied to other projects. The work done in each task also leveraged other opportunities to restore habitat and participate in community outreach activities. The first section of this final chapter addresses the accomplishments of the tasks. The second section addresses some of the lessons learned throughout the project.

Key Accomplishments

- nearly 1,000 linear feet of streambank stabilization work

- direct participation of over 400 students during the 2 1/2 year project

- publicity and raised awareness of Cazenovia Creek and the Buffalo River Watershed issues

- over 2,000 students indirectly participated through complementary programs like the Great Lakes Student Summit, Earth Day Expo, and Earth Day T-Shirt design contest

- two teacher training events

- evolution into ongoing program (Connecting To Learn) as a new vehicle to continue the goals and objectives of the Cazenovia Creek project

- Individual school participation:

1. Winchester Elementary School, Ms. Gail Hall

One of the first schools involved with the project. Winchester hosted two lab days, performed 3 days of streambank restoration and water quality testing at the West Seneca Soccer Complex, utilized the EnviroScape watershed model to learn about the Cazenovia Creek Watershed, appeared in the local paper several times, and teacher Ms. Gail Hall helped implement a new Land & Water Unit into her classroom based on the Cazenovia Creek program. The "Winchester Aquanauts" have proven to be the most energetic and enthusiastic classroom involved with the project. They will continue stewardship of Cazenovia Creek as they were chosen to be one of the five pilot schools for the Connecting To Learn Program.

2. Holland Central High School, Ms. Susan Grieser

Holland students studied aerial photos of the watershed and performed water quality testing in their town. They discovered and reported an illegal discharge in to the Creek and learned about the Clean Water Act and permit process. Students assisted with the streambank stabilization at Kissing Bridge Ski Area.

3. The Gow School, Mr. Dale Hazen

Even though Dale Hazen's Gow students have learning disabilities, they proved to be good role models and taught many of the younger students about the micro-organisms and invertebrates that rely on the Creek to survive. The boys participated in streambank stabilization in south Wales, and were instructors during the Lab Day in 2001. They continued to study the creek as it runs through the campus property and share their findings with the other students in the school.

4. Potters Road Elementary School, Mr. Bill O'Shei

Bill O'Shei's students were introduced to the concept of a watershed for the first time with a presentation of the EnviroScape Watershed model. They learned quickly and also participated in water quality testing and streambank stabilization at Cazenovia Park. A photo taken of the Potters Road students planting willow stakes won an honorable mention by the National Association of Conservation Districts as part of their contest for images that best depict conservation.

5. School #59 - Science Magnet School, Ms. Sharon Pikul

Ms. Pikul's classrooms have been involved with environmental education programs with DEP in the past and it was not difficult to launch the program in the Science Magnet school during the Fall of 2001. After September 11, the students were not permitted to leave school grounds, so DEP staff performed an EnviroScape presentation and did water quality testing in-class. Soon after, the Buffalo School Board claimed a $9 million budget deficit, and practically all extracurricular activities were eliminated. Over 400 teachers were laid-off city-wide and teachers, involved with ongoing labor disputes, were not able to commit the time or energy to the program for the remainder of the year. Ms. Pikul does intend on bringing her students to the 2003 Great Lakes Student Summit where they will display and present their research on water quality.

6. Main Street Elementary School, Dr. John Newton

Dr. John has incorporated the study of Cazenovia Creek into his classroom for the past several years and was one of the teachers instrumental in creating this grant program. His classrooms participated in day-long watershed tours and restoration field trips. The students shared their classroom study with the rest of the school, their parents and the community through local newspapers. Dr. John will continue his annual Cazenovia Creek treks in the years to come and is a great example of a teacher dedicated to creating a sense of stewardship for the environment into his students.

7. Buffalo Public School #71, Ms. Mary Jean Syrek

Ms. Syrek moved to School #71 from the Science Magnet School for the 2001-2002 school year. Unfortunately the sixth grade classroom exists in a school that is considered "under review" due to poor student performance. The students "had very little knowledge of environmental science and the word stewardship was not in their vocabulary". Ms. Syrek introduced the concept of watersheds to them first through wetlands and curriculum that she implemented in her previous school. After several days of instruction, each student created his or her own "paper wetland". The students were not able to leave school grounds and the newly placed school principal did not permit any additional classroom instruction other than Reading Writing and Speaking. Even though School #71 did not participate fully in the program, Ms. Syrek does believe that "what we did will make an impact on these students in the way they view our waters around us."

8. The Park School of Buffalo, Mrs. Beth Schoelkopf

Mrs. Schoelkopf learned of the Cazenovia Creek Habitat Restoration and Stewardship Project through the efforts of Ellen Ilardo, SWCD staff. The Park School became involved in the spring of 2002 by offering to do field work as part of their science curriculum. Students cut down Japanese knotweed and planted streamco willow and red osier dogwood seedlings. The Park School students will also be participating in the 2003 Great Lakes Student Summit.

9. Waterfront Elementary School, Ms. Dianne Johnson

The 2001-2002 school year was also the first year for Waterfront Elementary students (Buffalo Public School #57). DEP and SWCD staff performed two in-class presentations at the Waterfront school, one to introduce the EnviroScape Watershed model, and the second to show aerial photos of the watershed and to perform water quality testing. Students also participated in a modified watershed bus tour, and visited the Cazenovia Park restoration area. Due to the Buffalo Public School financial crisis and the reorganization of Ms. Johnson's classroom, School #57 was unable to continue formally on the project during the spring semester of 2002.

Lessons Learned

- Accountability is the Key. During the different stages of the project it became obvious that because there was no written agreement or Memorandum of Understanding it led to the lack of accountability by the selected teachers and lack of buy-in from the administrators. The spin-off program, "WNY: Connecting To Learn", will avoid this mistake by requiring all participating schools and teachers to sign a written agreement with clearly defined goals and responsibilities. Also, administrators for each district will be consulted prior to the implementation of the program.

- Follow-through is a must. The plantings and streambank stabilization was successful only because follow-up maintenance and replacement plantings were done two years in a row. This also helped develop the sense of stewardship for the students at their adopted sites. The Soil and Water Conservation District was an ideal partner to delegate this responsibility and offered accountability.

- Program implementation must be flexible. Teachers should be given the flexibility to implement the program based on the skill level of their students and the time available to commit to the project. A one-size-fits-all program will not work for a diverse audience. The students easily identify with local ecological values and concerns.

- Partnerships do not maintain themselves. It takes hard work and persistence to maintain positive partnerships. Though some partners were not able to live up to their verbal commitments the relationships remained positive. This is important for future collaborations, especially when coupled with the policy of Lesson #1.

- Create opportunity for continuation of project without immediate oversight. Enabling teachers and communities to maintain the program on their own without outside funding or management. Making yourself available for continued advice or future outreach events gives the teachers the confidence to maintain the program on their own. Avoid the tendency to "abandon" partners once the funding has run out.

Attachments

- Project Map (PDF) ( pp, 342 K)

- Planting Sites 2001-2001 (PDF) ( pp 401 K)

- Adams Property (PDF) ( pp, 310 K)

- Aurora Park Health Care Facility (PDF) ( pp, 321 K)

- Cazenovia Park (PDF) ( pp, 425 K)

- Kissing Bridge Ski Center (PDF) ( pp, 342 K)

- West Seneca Soccer Complex (PDF) ( pp, 440 K)

![[logo] US EPA](../gif/logo_epaseal.gif)