William K. Reilly: Oral History Interview

Foreword

This publication is the fourth in a series of interviews of EPA leaders that includes William Ruckelshaus, Russell Train, and Alvin Alm. The EPA history program undertook this project to preserve, distill, and disseminate the main experiences and insights of the men and women who have led the Agency. EPA decision makers and staff, related government entities, the environmental community, scholars and the general public will all profit from these recollections. Separately, each of the interviews will describe the perspectives of particular leaders. Collectively, these reminiscences will illustrate the dynamic nature of EPA's historic mission; the personalities and institutions which have shaped its outlook; the context of the times in which it operated; and some of the Agency's principal achievements and shortcomings.

The techniques used to prepare the EPA oral history series conform to the practices commonly observed by professional historians. The questions, submitted in advance, are broad and open-ended, and the answers are preserved on audio tape. Once transcripts of the recordings are completed, the History Program staff edits the manuscripts to improve clarity, factual accuracy, and logical progression. The finished manuscripts are then returned to the interviewees, who may alter the text to eliminate errors made during the transcription of the tapes, or during the editorial phase of preparation.

A collaborative work such as this incurs many debts. Kathy Petruccelli, Director of EPA's Management and Organization Division, provided the leadership to support the history program. Her superiors, who have changed over the course of the period in which this interview has been produced, John Chamberlin, Director of the Office of Administration and Jonathan Z. Cannon, Assistant Administrator for Administration and Resources Management provided the funds. Susan Denning and Daphne Williams performed invaluable proofreading and logistical services. Finally, the crucial contributions of two EPA Administrators must be recognized: Carol Browner, who has seen fit to continue the EPA History Program in the face of tight budgetary times; and William K. Reilly himself who not only has provided a candid and highly insightful interview but also was responsible for creating the EPA History Program.

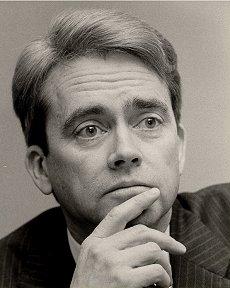

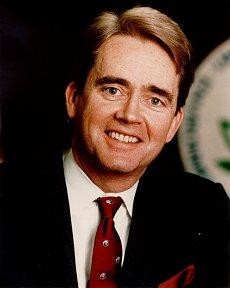

EPA Administrator William K. Reilly

EPA Administrator William K. ReillyBiography

William K. Reilly (b. Jan. 28, 1940) served as the seventh Senate confirmed EPA Administrator between February 8, 1989, and December 31, 1992. Born in Decatur, Illinois, into a conservative, deeply religious household, Reilly was strongly influenced by his father, a highway construction steel merchant, who impressed upon him an interest in land, history (especially that of Abraham Lincoln's Illinois days), and justice through the example he set while young Reilly accompanied him to state and county auctions to peddle his steel culverts and bridge materials. Reilly's father then led his family from Illinois to South Texas when William Reilly was 10. There Reilly learned to appreciate the unique cultural and environmental problems associated with transnational environmental affairs.

From the Rio Grande Valley, the Reillys moved to Fall River, Massachusetts, where he finished high school at Durfee High School. From Durfee he went on to Yale where he earned a B.A. in History. During his Yale years, Reilly took advantage of Yale's junior year abroad program to study in France. Reilly then earned a law degree from Harvard, completing a thesis on land reform in Chile. After law school, Reilly entered the Army and served a tour of duty (1966-1967) in Europe with an intelligence unit planning for the evacuation of U.S. troops from France. During that time, he married Elizabeth Buxton.

After completing his military service, Reilly returned to school at Columbia, where he earned a Masters degree in urban planning. In 1968, fresh from planning school and a four month project in Turkey, Reilly went to work for Urban America, Inc., where he worked to integrate century old concerns for urban beautification with the concerns brought to the forefront of the American conscience by the civil rights movement - concerns which would grow into the environmental justice movement with which he dealt during his EPA Administration.

In 1970, Reilly became a senior staff member of the President's Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) under Russell Train, who would later become the second EPA Administrator in 1972. Reilly moved from CEQ to become President of The Conservation Foundation, which merged with World Wildlife Fund (WWF) in 1985. After the merger, he served as President of World Wildlife Fund until taking over the helm at EPA in 1989.

As the following interview will show, the Reilly Administration accomplished several important tasks between 1989 and 1992. EPA oversaw the crafting of new Clean Air Act Amendments in 1990. It pushed for leadership in international environmental affairs in the face of global political changes by establishing liaisons in eastern Europe, participating in trade negotiations to ensure that the environment was considered during the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs, and encouraged the Agency to play a larger role in working with Mexico to address problems along the Mexican border both in environmentally and socially responsible ways.

Reilly also encouraged EPA to continue to work with the regulated community to find voluntary ways to go beyond mandated emissions standards. Reilly also encouraged EPA to address regional pollution problems which forced the Agency to strive to design cross-media regulatory strategies. These strategies had been discussed but deemed too unmanageable and complex to devote vast amounts of energy in the face of more pressing needs by previous Administrations.

Perhaps the most significant failure of the Reilly Administration, as Reilly suggests below, was that EPA was unable to garner the unalloyed support of the Bush Administration during the second half of that Administration's term. This was largely due to the inability of the Agency to muster the politically valuable praise of the Administration's environmental efforts by environmental organizations. As a result, the Bush Administration chose to work more closely with elements of its constituency that would provide political support during the 1992 election season. As a result, EPA found its agenda stifled in the White House and its credibility compromised before Congress.

After leaving the Agency during the final days of 1992, Reilly returned to World Wildlife Fund. From his office in that institution's headquarters, Reilly summed up his time at EPA by saying:

I find myself introduced, sometimes, as the voice that cried in the wilderness, as someone who tried to be the conscience of the Bush Administration on the environment. I went into that job with no illusions. I knew all of my predecessors; I knew how much conflict there had been and how many disappointments some of them had had in their times. In fact, I had many more than my share of good days. I remember Bill Ruckelshaus said as he announced his retirement, his resignation from EPA, that an EPA Administrator gets two days in the sun, the day he's announced and the day he leaves, and everything in between is rain.

That was not true for me. I had a lot of sunny days and I owe them to George Bush and. . . . it is thanks largely to the quality of the people who work at EPA, their zeal, their commitment, the fact that for them it's not just a job. They really believe in what they're doing and that they are doing something fundamentally important. That is what made our four years a very productive and exciting time. It's a time that EPA professionals, and the country beyond Washington, will look back on as a time of enormous creativity and energy and achievement in the environment. So, I was happy to have been along for that ride.

Interview

[SESSION 1: July 26, 1993, World Wildlife Fund Headquarters, Washington, D.C.]

Early life

Q: Mr. Reilly, would you please describe for me your upbringing, your early life and your education?

MR. REILLY: I was born in Decatur, Illinois, into a very close-knit, very religious, and very conservative family. My father was in business for himself. He sold steel - bridge materials, reinforcing bars, and metal culvert through his own Highway Supply Company. And my mother worked very closely with him. She was his bookkeeper, accountant, and partner. I had one older sister, four and a half years older than I, who is now a teacher outside of Chicago.

I lived for 10 years in Decatur, Illinois - downstate, Illinois - a city then of about 80,000 population; it's not too much more now. I grew up surrounded by Lincoln memorabilia and memories. My father sort of rode the circuit, just as Lincoln did, but for a different purpose. He traveled to county lettings - auctions - and state lettings and township lettings to sell his materials. Whenever we would pass a Lincoln marker we would stop. The Lincoln-Douglas debates took place in that area. Every single courthouse had its Lincoln memorabilia because he, typically, argued cases in those courthouses, or their predecessors. It's farm country and we had a farm. I spent some time on that. I went to parochial schools there, Catholic schools.

When I was ten, we moved to Texas, southern Texas, largely because a big steel strike in 1949 pretty much put my father's business on hold for four or five months - he didn't have anything to sell. We relocated to the Rio Grande Valley. My father was, for a little while, working for Dow Chemical. Then he went to work on his own as a contractor and did some construction. I remember that was the time when I became familiar with some of the problems that we now call colonias - these unsewered communities without any services at all, typically of undocumented aliens, or first-generation Mexican-Americans, along the border.

My father employed some undocumented workers. In fact, he got in trouble with the local construction contractor establishment because he paid them too much. I remember that we used to drive out in the country to pick them up in the morning and then drive them back out in the evening. I saw the abject poverty that they lived in. I got to know some, one became a good friend. Neither of us had many friends then in Texas. He was in his twenties, I was then probably 11. His name was Dom Juan Garza.

Whenever he was picked up by the Bureau of Immigration and taken to Mexico, he would reappear within a few days, having walked all night, if necessary, and ready to do anything - pick grapefruit or work at the motel where I first met him and where he was a worker. I developed some limited knowledge, but a lot of affection and respect and sympathy for Mexicans. I think that affected my later priority on some of those issues at EPA. One of the proudest things I did was to help get $50 million for colonias in the last Bush budget - and a lot of money for the border. I worked hard on the North American Free Trade Agreement, too.

I lived in the Rio Grande Valley for two years. It didn't really work too well for my father economically there. We finally then moved to northern Illinois. By that time he was quite ill; he had serious ulcers. After another two years, when I lived in St. Charles, Illinois, he had one of the first operations to remove most of his stomach. To recuperate from that, he went back to live with his sister in Fall River, Massachusetts. By that time my sister was off in college and my mother and I went with my father.

When he was finally recovered and ready to go back to Illinois, I just stayed behind because I had started high school and was doing well there. He left me there in the care of my aunt. So, I went to a large public high school in Massachusetts for four years, Durfee High. I'd go out and work, drive for him, in Illinois in the summertime. When I finished high school, I went to Yale. I spent my junior year in France and then after that went to Harvard Law School, followed by half a year or so in law practice, two years in the Army, and then another year and a half in school, at Columbia, studying urban planning.

So, I've had somewhat of a wandering up-bringing in various parts of the country, which I must say I never minded. I always thought that the moves we made were pretty interesting, the parts of the country I lived in, the Middle West and its prairie and farm country and the German-Irish settlement influence, and Texas, which was very heavily Hispanic - even then, the city I lived in, Harlingen, was about 50 percent Hispanic. Then, up to the northeast, to Fall River, which had the only French daily newspaper in the United States at that time, had twenty-some French-speaking Catholic churches and another twenty-some Portuguese-speaking churches and a lot of Italian-speaking churches!

A very large ethnic population - Syrians, Lebanese, Jews; a really fascinating melting pot to be exposed to - very different from the Midwest where I had begun life. So, I thought each of those moves was enriching in one respect or another. The Fall River era was the time I came to love the sea and came to know Cape Cod and Newport, Rhode Island, Providence, Mount Hope Bay, and some of those areas. My family vacationed there, and most of my aunts and uncles and cousins lived around there.

Anyway, after Harvard I went to practice law for a little while in Chicago, but had a commitment to go in the Army so I took the bar exam in both Massachusetts and Illinois, and then went into the Army. I went to the Infantry Officers School in Ft. Benning, Georgia; Intelligence Officers School in Baltimore, Maryland, Ft. Holabird; and had orders to Vietnam much of that time. Then, at the last minute, my orders were changed and I was sent to Germany with a little group of sixteen or seventeen - the first intelligence officers' class in two or three years to have been sent to Europe, because by that time we were depleting our intelligence officer numbers in NATO with everyone going to Vietnam.

My responsibility was to help plan the quick departure of our forces, or at least the Army Intelligence component of them, from France after de Gaulle gave the U.S. forces 90 days to get out. My knowledge of French and being a lawyer had a very practical advantage: it resulted in my being assigned very interesting work in Europe. I did that and then went to German Language School as part of my Army experience in Europe.

When I had fewer than 13 months to serve, less than the standard Vietnam tour of duty, and thus could no longer be sent there, I came home to get married to Elizabeth Buxton, a woman I had met at Harvard. We were married at St. Thomas More Chapel at Yale, where her father was a professor and chairman of the Psychology Department. After another year in Germany, I came back to a different country, really, in early 1968. The place was very different from what it had been when I left. The anti-war movement was going strong, there was a lot of anti-authority feeling in the schools - in fact, I was scarcely at Columbia a few months when Mark Rudd and the Students for a Democratic Society shut it down, beginning with the school I was in, the Architecture School where I was an Urban Planning student.

For a few days I was annoyed about that, but then I realized this was a marvelous education. So, I used to go up to the Columbia campus every day and just listen to the speeches, whether they were by Mark Rudd and his colleagues in SDS, or Black Panthers, or whoever was holding forth that day. I went to Columbia because of Charles Abrams, a really great man who had written Man's Struggle for Shelter in An Urbanizing World. He was an architect of the 1968 Housing Bill with Senator Percy and with the HUD Secretary. I did three semesters there, after which they awarded me a Masters degree.

I spent a summer working on a regional planning project in Turkey, on which my wife accompanied me. She had worked for the City Planning Department of New Haven and had more experience than I had. I thought at that time I wanted to be some kind of international urban planner and consultant. But in Turkey we experienced very strong anti-American feeling. Our new ambassador was fresh from the Vietnam pacification program Ambassador Komer, and his car was turned over and burned on his first visit to the university with which we were affiliated, Middle East Technical University.

That summer's experience indicated to me that it wasn't a good time for Americans to be going around the world telling other people how to behave. So I came back and ended up going to work for something called Urban America, Incorporated, which I thought I would just do for a year or so before going back to my law practice in Chicago. As it turned out, I never went back. Urban America, Inc. merged with the National Urban Coalition. Then, the President's Council on Environmental Quality, which was setting up and looking for a land use lawyer, went to my old law firm for advice about whom to pick. They suggested me.

So, I found myself one of the Council's first staff members under Russell Train and was given the job of helping draft the regulations - they were then guidelines - implementing the National Environmental Policy Act and the Environmental Impact Statement procedures. I also drafted a National Land Use Policy Act. That was the only one of the big legislative proposals on which we worked in the early 1970s that did not make it into law. The Coastal Zone Management Act is essentially the same bill that I had drafted, based on the American Law Institute's Model Land Development Code. So, we got a piece of it, a grant incentive program for the coast but not for the whole country.

After two years there, I was invited to direct a task force on land use for the President's Commission on Environmental Quality, chaired by Laurence S. Rockefeller. We produced a report in 1973, The Use of Land: A Citizen's Policy Guide to Urban Growth, which went through three printings and sold 50,000 copies. I accepted an invitation then to become President of The Conservation Foundation. In 1985, it affiliated with World Wildlife Fund and later merged completely. In 1985, I became President of both institutions. That's where I was when President Bush asked me to become EPA Administrator. That's probably more than you wanted to know.

Interest in Land Use Management

Q: No, that was very thorough. It covered several questions. I do want to go back just a second, though. You earned your Juris doctorate and then returned from Europe and earned a masters in urban planning. Reading your resume, it seemed to me that there was a big jump there. Was there something that had happened before going into the military or during the time you were in the military that encouraged an interest in land use management? Can you explain that?

MR. REILLY: Well, I was always interested in land and I have often tried to figure out why that was - whether it was because we had a farm early on and I spent a lot of time there, or because my father was interested in land. We used to look at land, he used to think about buying it - he liked to think about buying a lot more property than he ever bought. I can remember looking at beautiful oceanfront property with him near Point Judith in Rhode Island.

I honestly don't know where the motivation came from, but I did my law school thesis on land reform in Chile, with Charles Harr. I worked one summer on a book with a team of people headed by Lawrence Wylie, who was then C. Douglas Dillon Professor of French Civilization at Harvard. The book we wrote was called Chanzeaux: Village d'Anjou, published by Harvard University Press in English and by Gallimard in French. Basically, my part of it was to write about land tenure, agricultural law, the passage of property to children, credit systems, how the French were trying to reassemble parcels that had been divided through generations of Napoleonic law.

In fact, I chose to go to work for Ross Hardies in Chicago, because they were the premier law firm dealing with land use issues, certainly in Chicago and probably in the country. I found myself working on gas rate regulation, which was also a large part of their practice. Later, I decided to go to planning school partly to get reintroduced to the country, having been away at a time of great social change and turmoil, but partly also to help ensure that if I did, or when I did, go back to the law firm, I would be used in the area of my interest because I would have a degree in urban planning.

Urban America, Incorporated, for which I worked following my studies at Columbia, was concerned with what seemed to me the two great themes in American city development: one was race and civil rights and the other was planning, the city beautiful movement - the Frederick Law Omsted tradition and the parks and the rest. Very few of our institutions have been successful at bridging the divide between those two concerns, social policy and development policy, generally, for the broader population. They tried to do that. I became an expert in how you prevent communities from using large lot zoning or minimum lot sizes to exclude minorities and poor people. At that time I didn't think that I knew very much about conservation law or how to protect land.

I can recall saying to Timothy Atkeson, who was my immediate boss at the Council when I started there - he was General Counsel and he later became my Assistant Administrator at EPA for International Activities in 1989 - I said to him, "I don't really know much about how you protect land from development. I'm really an expert at breaking down restrictive procedures and laws." He smiled and said, "Well, it's really just the oher side of the same coin, isn't it?" And, of course, it is.

I found myself then working on protection schemes - but not completely. With the help of Fred Bosselman, a Ross Hardies lawyer, I drafted a federal legislative proposal to provide funds to communities to protect what we called areas of critical environmental concern and also to ensure that "development of regional benefit" be accommodated, even against the wishes of localities that resisted it. It was a balanced approach, which I think we have to have in our land use and development law. So, I kind of sidled into the conservation side of law and can't say that this was a charted course or a direct route, but it happened to be mine.

Council on Environmental Quality

Q: You told me a little bit about how you became involved in the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ); was this the first encounter you had with Russell Train?

MR. REILLY: Yes. I remember going to visit him at the Interior Department when he was Undersecretary there, just prior to his taking up his new position as CEQ Chairman, and having an interview with him after I had been interviewed by Timothy Atkeson. Atkeson told me that I should tackle him as he came through the hallway there. He came through a little out of breath - coming from the Congress, I think - and I immediately jumped up and started to speak to him.

"In a minute, in a minute," he said, "let me catch my breath, I'll call for you in a few minutes."

I can remember, in fact, the first conversation I overheard with him. Someone said to him, "We're going to have a phone installed in your car this week," and he said, "Good Lord, why do you want to do that, it's the only peace and quiet I ever get." When I served at EPA, I discovered why he might not have wanted a phone in his car. Truly the only peace and quiet you get in public life is traveling in an airplane, although now they're getting phones in planes, too.

He called for me and then interviewed me. We had a very nice interview and always got on well. I became not only a land use staff member at the Council, but I ended up writing a number of speeches on other issues for him as well. He became a mentor to me. I suppose if I have two in public life, they are Russell Train and Bill Ruckelshaus.

In fact, Train has had most of the jobs that I have had for the last 20 years. He preceded me as President of The Conservation Foundation, as President of World Wildlife Fund, as EPA Administrator. I've not gone on the tax court and I don't intend to - not that they would have me. But, I have enormous respect for him and have learned a great deal from him.

Other Mentors

Q: Would you say that you had any other mentors?

MR. REILLY: I certainly had another mentor in a man named John Bross, John Adams Bross, who was a CIA official and member of The Conservation Foundation Board from 1974 on. He was thoughtful, very modest, and very cultivated in an unassuming way. He had a wry, twinkly, humorous attitude towards a lot of things and particularly was able to be funny about the things that a lot of people would be pompous about - things that he knew and had experienced. He knew Shakespeare and he knew art and he knew government and politicians and he knew people, he'd known the important ones who'd come through Washington over the last 25 years or so.

I can recall many a fine lunch with him where I just soaked up the kind of wisdom he tossed off nonchalantly. I remember, in fact, I went directly from my announcement as EPA Administrator at the White House with President Bush to his hospital room and talked to him about everything. He'd seen it on television. He had a bad case, then, of cancer. It had him in the hospital, but he recovered for another couple of years and died, just about two years ago, now.

My father, of course, has been a very important figure in my life, too. Very strong, very generous, capable of being severe but also quite compassionate to people who need help. Very religious. I often think how much easier I've had it than he had it. He was a child of the Depression. As a teenager he worked on the Fall River Line on a boat that went back and forth from Fall River to New York. He was also a dining car steward on the Pennsylvania Railroad. Then he went out on his own to Illinois, very bravely, without any health insurance or benefits or retirement or any security or clear prospects at all. It took him two or three years before he made any money at all. He pretty much was supported by his brother who was also in the business and would give him an advance for the week.

He finally had a big success at the Illinois State Fair where he sold a big pile of steel culvert several times over, metal culverts, to township commissioners responsible for country roads and drainage who were coming through. He was able to make that the start of his success in business. But he worked very, very hard for what he got and paid the price in his health.

He later recovered that and has been a very successful man by any measure. But I think he has the sort of divine discontent that characterizes a lot of artists and perfectionists. He sees a lot of ways that things could have been better. He gave me a great education and obviously valued that tremendously. He also made great sacrifices, not just financial, but in allowing me to stay in Massachusetts where he thought I was going to get a better high school education than if I had moved around with him, which is certainly true.

What he, and I, did was always with the great support of my mother, who is a very warm, loving, tolerant person and who has no rough edges. She just communicated a great love and security to me that probably has a good deal to do with my sense that life would go on and it would unfold in ways that I would probably like - which it has. Successful, confident men tend not to talk much about their mothers. I've noticed, though, more than anyone it's mothers who make for secure sons, I think. Unlike my father, my mother radiated a quiet, reassuring faith in the future, and a sunny optimism. Like my mother, I don't worry a lot.

Q: What would you say you've learned from Mr. Ruckelshaus?

MR. REILLY: Ruckelshaus had a very clear concept of the need not only to ensure integrity in public service, in government, as a government official, but also to communicate to the country what a government agency was doing and why. I saw my job, in very large part in 1989, as one of communication. At that time, and certainly now, we had more diffuse anxieties in the country than we could ever craft policies and programs to address.

The public is very concerned about risk - particularly the involuntary kind, the kind that they believe they're subjected to by chemicals in their food or pollutants in the air or water. They need to have all of that put in perspective and they need to embrace some sense of proportion. People need to have some guidance from a trusted source about what matters and what doesn't, or rather about what matters most and what matters less. That is necessary for EPA to do its job with respect and credibility.

We heard in 1989, as we continue to hear, that EPA isn't doing this or that or it's missing this or that milestone. Of course, it's always true. It's a consequence of so many responsibilities that have been given the Agency without sufficient authority or resources to carry them out. But ultimately, government is accountable to people and it's people who are causing their Congressional representatives to write these bills and to continue to write them, even though the money isn't there any longer. In fact, the EPA budget's gone down this year very substantially from what the last Bush budget was. The only way to do that is to cause people to believe fundamentally that there is integrity in the process - those in government do know what they're doing.

Second of all, some things pose much less risk to people than others and officials need to acknowledge that in their public representations to the Congress and finally in the budgets and priorities that the Agency proposes. The only way that you arrive at that point is through constant communication. I think that Ruckelshaus had a clear sense of that.

Certainly at the very beginning of EPA he spent considerable time on it and, when he came back in '83, he spent even more time on that. I believe in that. He was not excessively focused on the Congress or on the internal workings of the bureaucracy, which happens to so many agency leaders. He recognized the broad country out there from which our mandate comes but also whose sense of priorities have shaped the program that needs reform.

International Interests

Q: You mentioned a bit earlier about going to Europe and then Turkey and experiencing those places. Would you say that was the origin of your keen interest in international work or would you say that came from something else?

MR. REILLY: The truth is that I think I developed my international interests as a high school student in Fall River, Massachusetts, who was just fascinated by some of the French convent girls who were sheltered from us non-French folks. I remember trying to crash the Franco-American dances and having people grill me at the door about "What's your name? What's your mother's name?" and then saying, "Well sorry, you can't come in here." There were five convent schools, I think then, and I eventually succeeded in dating one of those girls. I was very interested in French and in France. When I applied to college, I only applied to two schools, Georgetown and Yale. I made it very clear in my application that their junior year abroad programs were part of what I was applying for. I was true to that; I went on to study in France.

I've spent a lot of time abroad in the course of my life. I worked a number of summers and then studied one full academic year in France. I spent one summer in Switzerland working for the United Nations while I was in law school. I spent one summer hitch-hiking all over Europe - I used to hitch-hike whenever I went there. In fact, I hitch-hiked one summer starting out in Paris across England to Wales, to Ireland and all around Ireland, back across England and then across Belgium and to Germany up to Stockholm and back from Stockholm almost down to Vienna. I learned a lot doing that - that's a good way to get to know a place.

I lived for a year and a quarter in Germany and went to language school there when I was in the Army. I lived for four months in Turkey, in 1968, when I went there on a regional planning project. I've had about 13 summer vacations in Italy. A friend has a place there that our family often goes to. I spent two weeks in Spain and two weeks in Mexico this past spring just working on language. I like Europe a lot and I've always thought it was very important. I was a history major in college, and believe, with DeGaulle, that "America is the daughter of Europe."

Europe is obviously the cradle of our civilization, our values, and our institutions. And I have become very interested in Latin America. When I was President of World Wildlife Fund that was my principal area of interest. Mexico and Brazil were WWF's two biggest programs and Central America was a large one. I then set out to learn Spanish and came to understand that part of the world much better.

I'm sure that the international interest was the reason why I gave such priority to some things at EPA - like the Border Plan, and the North American Free Trade Agreement, for which I testified six or seven times. I discovered, incidentally, that, as far as I could ascertain, no environmental minister from any country had ever gotten involved in a trade treaty, nor had an EPA Administrator testified on a trade treaty. I thought that the NAFTA was very important to the environment but also very important to our Mexican-American relationship and the stability of Mexico. I continue to give a high priority to that and one of the public lectures I deliver in the fall at Stanford will be on international institutions, another one will be on trade and the environment, both of them very international in orientation.

We are part of a larger world and the environment of that world is one that cannot be managed successfully by one country. It cannot be managed because the pollutants travel and don't respect borders. It also cannot be managed because we are going to be in a web of trade relationships for which the environment can be misused for protectionist purposes, to exclude goods by claiming their production harms the environment, or to create a competitive advantage at the expense of the environment - by having lax controls that make your products cheaper, i.e., by creating a pollution haven.

As we gradually relieve the tariff burdens on trade, countries will pursue their economic interests through other means. Very often those other means will be by saying, "Well, we're not clamping down on beef hormones to keep your beef out, but rather because it's environmentally unacceptable, and so forth." That will require people who are concerned about the environment to become much more knowledgeable about trade and to come to respect the need for free trade because it advances the environment, aside from advancing other aspects of welfare.

But we need to advance trade interests with a sense of protection for those things that we value and don't want to see unraveled - which trade people, often insensitive to environmental controls, can unwittingly unravel. I don't know how I got there. Your question didn't necessarily lead all over there, did it?

The Conservation Foundation and World Wildlife Fund

Q: It didn't necessarily, but that was a good path. What did you learn from your earlier experiences with The Conservation Foundation and World Wildlife Fund?

MR. REILLY: The Conservation Foundation's niche was to recognize those issues on which the country was stalemated or which were not being very successfully addressed but in which we saw an opportunity. In the mid-seventies when the oil shocks hit and the economic crisis occurred, there was a sense that we had bitten off quite a lot in the environment. We had passed laws on air and water and strip mining and toxic substances and coastal zone management and endangered species - many of them quite ambitious and virtually all of them more expensive and, in some cases more obstructive of other interests, than had been understood.

The economic community, which was capable of helping us refine and make efficient many of those laws, had pretty much opted out of their early formulation. They had fought them so bitterly that they weren't really at the table in helping craft regulations. Yet, it seemed to me, that the environmental community could not take those laws much further alone, and certainly couldn't ensure their successful, efficient implementation without the involvement of business.

These laws were coming under heavy fire for their cost and bureaucracy, particularly at a time of national economic difficulty. The business community was being driven crazy by some of the early costs of regulation, the demands being placed on them, and also by the public image they were getting as obstructionists. And yet, any reasonable reading of the polls, it seemed to me, indicated that the nation was wedded to environmental values, wanted to see those laws kept, and, in some cases, wanted to see them strengthened. The environment was entering the core values, as the pollster, Bob Teeter, has put it, of our people.

If you think of those two sets of interests - of environmentalists wanting to see the laws they had championed work, and industrialists realizing that environmentalism was here to stay and therefore the realistic goal was to achieve more cost-effective implementation - you realize there is a common basis for getting some agreements between business and environmental groups.

Based upon that, in 1974 we developed a program in business and the environment which tried to get consensus on critical, divisive issues such as on road building in national forests, which environmentalists prefer to keep as little intrusive as possible and which the timber industry also doesn't want to have to build wider or more expensively than necessary. Toxic substances control and the early implementation of a new toxics law was another issue we took on then. We sponsored a project on natural gas with the Committee on Economic Development. Project participants advocated deregulating natural gas prices in order to bring on a fuel that would really help the environment and was in plentiful supply in the United States.

We had a program on groundwater chaired by Governor Babbitt that included business leaders, environmentalists, state and Federal officials. It designed measures that would protect groundwater and give some clarity and certainty to the development process. Babbitt had done that very well in Arizona. We followed that project up with a major task force on wetlands, chaired by Governor Kean of New Jersey, and that was designed to try to bring people together on that very divisive subject. Out of that group came the recommendation for no net loss of wetlands, the recommendation that President Bush committed to in the 1988 campaign and later became a priority of EPA and the Administration. The groundwater report fed into policies that we implemented at EPA also. Those reports had far-reaching impact.

The Conservation Foundation's operating style was relatively quiet, very inclusive, with a sense that we wanted to look for ways to bring people together around policies that would endure. It always struck me as a conservationist that those policies will not endure that do not have the adherence of the economic sector. We simply must embrace economics in our environmental formulation, just as I think the economic sector has to factor in the environment and health now to a degree that it did not used to do, if we're to have a sustainable economy and also public support and acceptance of a lot of what the industrial sector does and wants to do. So, that was our philosophy.

World Wildlife Fund, of course, was almost exclusively an international institution. It was active in Latin America, in Africa and Asia. It, too, largely avoided stridency and confrontation. We worked in some countries with rotten governments, with undemocratic systems, that we had to make peace with if we were going to continue to operate. We worked through local institutions, generally. We tried to build up non-governmental organizations and local pressure groups in many countries that lacked them.

We did not, ourselves, go in making noise to their public as Americans, but rather tried to get locals to study and to appreciate their environmental treasures, in many cases, their wildlife, their flora and fauna. We had access to decision-makers to a degree that most environmental groups did not, simply because the organization was a worldwide group with then 24 - now, I think, 28 - national organizations headed internationally by Prince Philip, with significant people on most of the national organization boards. So we had a good bit of influence.

For a conservation organization, we also had a fair amount of money and resources. But, compared to the size of the problem or to what the economic sector deploys, we didn't amount to a rounding error. I gave, again, with that institution, a priority to bringing economics and the environment together. Our flagship program there was something called "Wild Lands and Human Needs," recognizing that the traditional approach to protecting animals, of punching a hole in the map or putting a fence around an area, wasn't going to work.

Hungry, needy, land-poor people can't be fenced out. Conservation must work for the people, the culture in which it finds itself. We had to find ways to accommodate the very legitimate development and economic demands of quite poor people who were multiplying in number, who were often poaching in these parks or going in for resources - like cutting down the timber or gold mining in Corcovado in Costa Rica. People living near those great reserves had to gain by them, had to see them as helpful to them. Very often we could do it - reconcile wildlife and human needs - with programs like eco-tourism or agro-forestry.

Timber could be harvested in areas adjacent to important wildlife preserves and cut and marketed by cooperatives. The object was to help people exploit the resources of their own environment but in a way that would allow them to continue to use and enjoy the environment over the long term, while conserving a critical mass of species of flora and fauna.

I heard this concept put very well by President Salinas of Mexico a few weeks ago. I accompanied him for three days as he was dedicating some new reserves in Mexico. In the Yucatan, deep in the jungle, with the camposinos as his audience, he said,

This forest is very valuable. The ancient monuments here are valuable - not just because people pay good money, which they do, to come see the monuments and enjoy the jungle, as important as the money is - not just for the wildlife, which is also very valuable, but it's not as valuable as you are. The reason to keep the forest is that out of the forest your ancestors and you have come. It has sustained the ground-water under it, it has created and made possible your culture and your society, and only if you keep it will it continue to do so for the children of your children.

I don't think I've ever heard a head of government speak so simply and persuasively and eloquently to the nature-culture relationship as he did. People believe him and that's one reason he's still popular in Mexico. That, essentially, was my, much less eloquently put, vision for World Wildlife Fund when I was there and one that I think we did a good bit to advance at that time.

Initial Perception of the Agency

Q: Before you came to EPA, what was your perception of the Agency?

MR. REILLY: You know, I didn't have a terribly good impression of EPA before I went there. I think that I had been exposed to two kinds of criticism. One is the stereotypical view held by much of the regulated sector, which views EPA as: excessively concerned about small risks; highly bureaucratic; ludicrously protective, sometimes; always overestimating threats to health; not very responsive to economic concerns; and very insensitive to cost-effectiveness. I shared some of that view. I think I partook also of the environmentalist critique of EPA, which is of a hide-bound, bureaucratic agency, deeply scarred by the Burford years, risk-averse, wrought up in its own systems in ways that cause decisions to take far longer than they should, unwilling to embrace finality - partly for reasons of bureaucratic anxiety that if you keep the decision going, you won't be subject to a nasty Congressional hearing or to criticism.

I had lunch one day a couple of weeks before I was sworn in as EPA Administrator with a veteran journalist, Guy Darst, an Associated Press reporter. He had been around forever and had covered a lot of agencies and said, "Well, you're going to the best."

"Really?" I said, "That's not the view on the street."

"EPA will make five decisions in the amount of time it would take Interior or Agriculture to make one, and they'd still screw it up. EPA is at the intersection of science and public policy and economics and health," he said, "and just has to keep turning out the decisions. There is no place to hide. That's the function and that has made the Agency very good at what it does. It's very sophisticated."

I must say, that was news to me at the time - that a very informed and quite objective observer would have that judgment. That's the judgment I took away from the agency-of a group of highly motivated professionals with a great deal of élan. One often hears people criticize that zeal and sometimes, I suppose, EPA may be guilty of having a bit much of it, but that's what makes it a joy to go to work there. It's one of those agencies where you get invigorated walking down the halls, not one where the adrenaline flows out your shoes after about 30 feet - and we certainly have those in the Federal establishment.

I remember a conversation with Interior Secretary Manuel Lujan one day. He was talking about the difficulty that the Secretary of the Interior has dealing with the Fish and Wildlife Service or the Park Service. He said "You give them an order and you have the feeling they're not going to carry it out until they check with God. Whereas the Bureau of Reclamation, or the Bureau of Mines, salutes and performs." Then he laughed and he said, "Oh, for a moment I forgot who I was talking to. All you have is people who take their orders from God."

You know what he means, and that's true. EPA is a place with a moral fervor that sometimes can be excessive. But, it is a place with commitment and, I think, a great degree of professionalism. I tried to broaden its perspective, somewhat, to make much more of economics, of prevention, of incentives rather than strictly holding people to account for doing bad. I encouraged it to think about how to motivate regulated industry, and about the whole larger world out there, the international environment, to which EPA can be so helpful.

EPA's prestige rises almost directly in proportion to the distance one gets from Washington. In the rest of the world, people do understand what many here at home don't, which is, EPA is the place you go to for information about the environment, for criteria documents, for health information, for the best science that we have on the health impact of pollutants, and the way to set standards, the best laboratory work on automobile pollution, and increasingly on a number of other issues like indoor air pollution.

EPA has more experience with remediation of toxic contamination than any other agency in the world. These are all cutting-edge problems - they require so little, relatively, of the U.S. government to be deeply, lastingly helpful to South America, to Russia and Eastern Europe, to China and Taiwan.

I can recall having sent two or three people to Latvia to deal with a spill in a river that provided their drinking water - a spill of some stuff that the Russians dropped in the water inadvertently but hadn't bothered to warn the Latvians about, even though the age of Glasnost had dawned. The Latvians detected an unfamiliar odor and figured out they had a problem and did not want Russian experts. We sent some professionals and I heard later from the Latvian President that this was the most important American mission since Lindbergh's visit there.

We helped Mexico when they had the big gas explosion and fire in Guadalajara; we sent a team to help Morocco cope with a big oil spill; we did those things, and buried the costs in programs. Our professionals returned invigorated, were animated, energized by their encounter with a real need in another country whose environmental problems are so much more egregious than our own. Thus, involvement with helping others was very useful to the Agency and a very inexpensive way for the United States to express what is one of the most benign qualities of our culture, our environmental aspirations and experience.

President Bush

Q: You talked a bit earlier about the process by which you became EPA Administrator. Could you describe that in more detail and talk about what qualities President Bush may have sought in an Administrator and any particular sponsors you may have had?

MR. REILLY: Well, you know, that history - I'm not sure I understand it all. I know that in the summer of 1988, Russell Train, who was then Chairman of World Wildlife Fund, hosted the Ruckelshauses at his house in Hobe Sound, Florida, I think in May or June. Not long after that he returned to say that he had had a conversation with Bill Ruckelshaus. He quoted Ruckelshaus as saying, "If our candidate George Bush becomes President, he's likely to turn to you and me for advice about who should be EPA Administrator and my advice would be Reilly. What would you think of that?"

Train, who just three years before had initiated with me a big merger of The Conservation Foundation and World Wildlife Fund, with me then taking over the organization as Chief Executive Officer, and him as Board Chairman, obviously wasn't going to find it convenient to see me run off to government. Nevertheless, he told Ruckelshaus that he couldn't disagree. Upon returning from Florida, he told me of the conversation with Ruckelshaus and he asked, "What would you do if that were offered to you?"

I said I'd say no.

I said I hadn't really completed what I had set out to do with WWF, there was a lot of continuing work necessary to make our two institutions mesh. I really liked what I was doing. I liked the international character of it. And, I just didn't know how serious George Bush would be about the environment, anyway.

So he said, "When a President asks you to do something, it's pretty hard to turn him down. So I'd just like to ask you to think about your succession here, how that would work, should this invitation come."

I didn't hear anything more about it until the day after the election. Ruckelshaus called me up and said, "Would you like to do something in this Administration?" He mentioned EPA Administrator and Interior Secretary.

I said, "No."

He said, "Well, if people were to talk to you, would you agree with me not to turn it down or say no until you get in front of the President-elect because he doesn't talk to enough people like you. If you have that encounter with him, you can probably have some influence on his thinking early on, whatever you do."

I think Ruckelshaus figured that if I ever got that close to the President, it would be pretty hard to say no to him. My wife later told me that she decided the previous June when she heard of the conversation with Train that I would do what the President wanted me to do. She didn't see me saying no.

I remember a lot of our friends would say, "How was it that when hardly any of your colleagues in Harvard Law School ever ended up in the Army, you did?" She would point to me and say, "Patriot." It was true. I thought you should serve. I came out of the Midwest and even though I didn't like the Vietnam War much, I thought one served the country in the military.

And when I finally did get in front of the President-elect, I found it impossible to say no to him. Someone had said to me in the transition - I guess Bob Teeter finally got in touch with me and talked with me about what they were looking for - and said, very frankly, that they were going to tilt one way at Interior and another way at EPA and that I'd come highly recommended by Ruckelshaus. I, however, went through that fall without any formal meetings other than the one Ruckelshaus conversation where he said he thought they would be getting in touch with me. They didn't call for at least a month or a month and a half. Then I began reading that I was one of the two hot candidates under consideration, but still no one had talked to me.

My friend, Phil Shabecoff, called me one day. He was the New York Times environmental correspondent. He said, "I have it on very good authority that you are on a short list of three. Do you know about this?"

"Nothing more than I read in the newspapers," I said.

"That's very strange," he said, "this comes from a good authority. But," he said, "there is something wrong with my EPA list."

"What's that?" I asked.

"Elizabeth Dole is on this list, and she's politically ambitious," he said.

"What does that mean?" I asked.

He said, "Well, you'd never go to EPA if you had any political aspirations. It would be the graveyard for those hopes." He talked about the position, said it was an impossible job. He said that it requires you to master more data and information than any job he'd ever covered. It's a thankless job. You'll make enemies, he said. You'll end up without any friends, probably, in your own community and you won't make anybody else happy. He later changed his mind and said that he had reconsidered and that he should have encouraged me to go there.

I guess I was finally called in early December. I had a meeting with Teeter and then was to meet with Craig Fuller, but he was ill. Finally, then, I was invited to meet with President-elect Bush. I had about 35 minutes with him with Craig Fuller present. At the end of that, he did not offer me the job. He said he wanted to check a few things first - although in the course of that conversation, he had asked Fuller, "Where do we stand on this?"

"It's ready to go, or," Fuller said, "you can talk to someone else if you want to."

"That won't be necessary," Bush said.

The next day he called me up, he'd been trying to hold the secret, obviously. About ten or eleven he called me up and asked me to be his EPA Administrator and invited me to come over about two and said he would announce it in public and introduce me to the White House press corps. I told him I would work to make him a great environmental President.

I never really knew a lot about his thinking, other than from one evening in the Netherlands when Mrs. Bush and the Queen of the Netherlands were talking at a State Dinner in the Netherlands and I was part of that conversation. Queen Beatrice asked Mrs. Bush where they had found me. She said to the Queen, "'For EPA,' George said, 'I want the best, nothing else. No politics, no partisanship, just the best we can find.' Everybody said, 'Well, if that's what you want, Bill Reilly's the person you want to get.'" That could have been very generous on Mrs. Bush's part, but that's the sum total of my exposure to their thinking about it all.

I remember Train said that he thought I would get on very well with Bush, that our temperaments would mesh well, and certainly they did. He and Mrs. Bush were very generous, very kind, to my wife, Libbie, our children Katherine and Margaret and me through all of that. They communicated even when we had difficulties with the White House Staff.

He had a fundamental confidence in what I was doing and when things mattered a great deal to me, he would take them seriously. He always kept his promise to provide access when I needed it to talk to him and kept a promise to ensure that I didn't get anybody I didn't want in any of the key jobs. As some of the current Cabinet are discovering, that is a very valuable commitment to have from the President and very few people get it. But, I got it.

He did say to me at our initial interview, there wasn't any more money for EPA, and that the budget would not be going up. He asked what that would do to my standing in the environmental community and whether I was prepared for that. In fact, we did a lot better than he had led me to expect we would because we increased EPA's operating funds by 54 percent on our watch and the overall budget by about 45 percent. That's a measure of Bush's support for which he didn't get much credit during his term, though the League of Conservation Voters later wrote approvingly of our budget performance.

Q: During that one hour meeting and subsequently, did he or any of the White House staff give you specific advice on what he expected you to do or not to do at EPA?

MR. REILLY: No, and it's interesting that you don't necessarily get that in top jobs. I don't believe my predecessors ever got a clear sense from their President of that. Bush expressed his own philosophy. He said, "I'm not a rape-and-ruin developer and I'm not for locking everything up, either." He said he believed in balance.

That's really my philosophy. It's one of integration and reconciliation of priorities. That's a philosophy I can subscribe to. It's really very close to my own. I'm sure that's the way Ruckelshaus had characterized me to him. He seemed very open to ideas when I talked to him. I remember that I thought, "Well, I don't know if I'm going to talk to him again or if I'm going to be offered or accept this job, but I'm sure going to use my time well."

So, I told him about "Debt for Nature," which I had been working on for two or three years, the concept of forgiving debt or writing down debt in hard currencies, dollars, and having some portion of the forgiven amount being applied to conservation in local soft currencies in the debtor country.

He said, "Well, that's a hell of an idea."

I remember thinking, "I've been working for three years on that and if I'd just gotten the President of the United States to think that it was a good idea, I'd really advanced the ball." Of course, it did reveal to me the enormous potential power in access to the President and in the kind of job he was talking about my taking. That certainly had an impact on me.

We talked about Cabinet status for the Agency. He was very frank and direct and said he didn't support it. He said that he thought there were too many in the Cabinet and he wanted a lean Cabinet, a small Cabinet, but he was open on the question. At one point he said, "Well, if we could do that in lieu of putting out millions of dollars in new budget outlays, that might be a good trade." It was a very congenial conversation.

[July 29, 1993]

Top EPA Personnel

Q: Mr. Reilly, the last time we spoke, you described your one-hour meeting with President Bush, as you were deliberating whether or not to take the job at EPA. Can you describe now your top personnel?

MR. REILLY: I can recall that Bill Ruckelshaus had indicated to me early on that there were two problems endemic to the White House-EPA relationship. One was the OMB regulatory review relationship and the other was personnel. I found that the promise that President Bush had made to me that there would be no one I didn't want at the Agency, which obviously meant that we both had a veto, was kept. It was hard slogging, there was a lot of negotiation. My first nominee was Terry Davies as Assistant Administrator for Policy. He was, I think, the lone Democrat in the crowd and he was the last one agreed to by the White House. White House personnel simply held hostage Terry Davies until they made sure the rest of the complement was to their liking.

I think that was a big mistake and they came to regret it. It meant that the Office of Policy, Planning and Evaluation had no champion and was not effectively represented in the formulation of the Clean Air Act. It might have been a somewhat different Act had they been included. The staff there was somewhat critical of parts of it. But, as Counsel to the President, Boyden Gray used to complain about not having OPPE involved in it, he was quick and generous in acknowledging that it was his and the White House's fault. They hadn't given me Terry Davies until the Clean Air Act had been forwarded to Congress.

Bill Rosenberg, a Michigan developer and former energy official in the Ford Administration, came to me with the very strong endorsement of Bob Teeter, who'd been central in the President's election. Rosenberg wanted to be Deputy, as I recall. Clearly his energy and aggressiveness and imagination would be valuable to the new organization. But, his lack of EPA and environmental experience did not, in my view, fit him so obviously for Deputy as it did for Assistant Administrator for Air, which is where we put him.

I thought his relationship with Teeter would bode very well for our working with the White House and his obvious energy would be a wonderful asset in seeing through the first major legislative program that we wanted. That proved correct, even though there later was considerable anxiety and hand-wringing about him in the White House. He did the job the President and I asked him to do and the President's domestic policy would have been much poorer without Bill Rosenberg. But he drew the lightning of resentment about our very strong Clean Air bill.

We chose LaJuana Wilcher for Assistant Administrator for Water. I can remember she came to me with the highest endorsement of Senator Mitch McConnell from Kentucky, who called to say that probably the Senator from New York or California or Illinois, frequently had candidates of great quality and distinction to press upon a government agency head, but he had never had one, as Senator from Kentucky, of the likes of LaJuana Wilcher. That got my attention, so I agreed to see her, even though I had all but decided on a different candidate, a Congressional aide.

I remember I asked her what she thought of my having begun the process to review for possible veto the Two Forks Dam, a huge project in Colorado. She looked very serious and paused and said, "I think it was a mistake." Well, you can imagine that was one of the most controversial decisions I had made. There was a very heated debate at that time within the Administration and in Congress about what I had done and a great concern about it in some quarters in Denver and other parts of the West.

For the prospective Assistant Administrator for Water to tell me to my face that she didn't agree with it, I thought was very brave and interesting. I respected her independence and obvious integrity. Clearing her was no problem because Senator McConnell had been one of the two Senators who had endorsed President Bush before the convention.

Tim Atkeson, the Assistant Administrator for International Activities, was a name whom the White House had already cleared on a list for the job. He was an old friend and colleague, much admired, of mine. I'd worked for him on the Council on Environmental Quality in the early '70s. So that was an easy choice.

For General Counsel, I can recall, it came down to two candidates. One was a lawyer with a New York City firm who, no doubt, would've done fine but to me lacked drive, didn't look particularly imaginative or energetic. The other was Don Elliott who was a very creative, positive can-do, law professor from Yale, an expert on administrative law and very much interested in economic incentives and pollution prevention and innovative new directions in environmental law. He was someone that colleagues found sometimes abrasive and professorial. He gave good service to me and I never regretted that choice. I thought he did an outstanding job.

Don Clay was a career figure. He was about my fourth choice, frankly, for Assistant Administrator for Waste. I was never confident that I could get him through the White House. In the end, White House Chief of Staff Sununu agreed to his appointment reluctantly late one evening. Sununu called me the next morning to say that he had changed his mind. I was able to say I had already offered the job to Clay. I remember Sununu said, "Well, he's part and parcel of that gang over there and I'm going to be watching him very closely. He's on probation as far as I'm concerned. If he steps out of line over the next six months, we're going to yank him."

In fact, Clay had built that marvelous air staff that Rosenberg wielded so effectively. He deserved a great deal of credit for that. He had the respect of people inside the Agency and I thought would immediately be perceived in the Congress as a non-political figure, a professional, which the Waste Office badly needed, given the history of scandals in the early '80s. I thought he also understood the need for reform of some of those laws. He hadn't grown up with them, he wasn't wedded to them, and he could rethink them. He also was a very good manager and that's one of the most difficult offices in the place to manage.

Linda Fisher was Chief of Staff to my predecessor, Lee Thomas. She also had been Assistant Administrator for Policy, Planning, and Evaluation. She had been very heavily involved in the reauthorization of the Superfund Law and had made some enemies in that, as anybody who is effective will. She was interested in international activities at the time, but I frankly thought that I wanted a new face there -- someone not identified with the previous Administration speaking for me internationally. But, I concluded that she would be very good at Pesticides and Toxic Substances. I think she is outstanding and is qualified to be a future Administrator. She knew the Agency well and was very effective. She won the trust of everybody who dealt with her. She gave me some of the most objective, and rational, and clear briefings of anyone. She was a key negotiator on the environmental provisions of the North American Free Trade Agreement. She is a star.

The Deputy is a slot that the White House paid a good deal of attention to and we actually had some arguments over it. There were a couple of candidates that the White House pressed on me whom I did not find suitable. One I'll tell you a story about. I didn't know the candidate personally and so I called Al Alm, former Deputy Administrator of EPA, to ask if he knew this person. He was in Boston at the time, in his office. He paused upon hearing the name and said, "I have in front of me the Boston Telephone Directory. If I open it at random and select a name, I will do a better job for you at finding a Deputy than the one you've mentioned." So, that took care of that.

I had interviewed Hank Habicht and thought that I wanted to find a place for him at the Agency. I had known him somewhat previously - had come in contact with him when he was Assistant Attorney General and then when Clean Sites Inc. was looking for a new President. He very much wanted to be Deputy and I thought we had a very consistent understanding of the needs facing the Agency and the role of the Deputy that I envisioned. I told the White House I didn't want their candidate, considered him weak and unqualified. The individual had some political support, but I wanted a real Deputy. They said, "Look, just take this person and keep him out on the road and have your Chief of Staff run the Agency."

I said, "I don't want to do that. I want a genuine Deputy who knows the place, who does the job, who is Mr. Inside, who is effective and respected, and who will work with me as a colleague." That's what I got in Hank Habicht. Beyond even my high expectations, Habicht proved outstanding. I think the Agency came to see him, having had some reservations at first because of his history as Assistant Attorney General in the Reagan years, as a thorough-going professional - insightful, sensitive, a very good manager, and a very bright prodder toward total quality management and toward reform of some of our laws.

He also proved to be extremely good at negotiating with the White House. He has a very attractive, even temperament and an obvious knowledge of the issues. He does his homework and speaks with quiet authority that is compelling. There have been a number of good Administrator-Deputy relationships going all the way back to Bill Ruckelshaus and Bob Fri; and then Ruckelshaus and Al Alm; this is in that league and I like to think is even better than that terrific record. Hank, obviously, is a future Administrator or equivalent, also.

The unsung hero of my Administration at EPA was Gordon Binder, my Chief of Staff. Gordon missed nothing, spotted problems and quietly fixed them, shaped up personnel, alerted me to various Agency weaknesses or threats, and faithfully communicated my views. He was always objective, could tell me unpleasant news, and had a masterly control of the paper flow. He had been with me for 19 years and knew I liked a taut, congenial team, with no backbiting, no friction costs owing to petty competitive games. No one was more helpful to me or to the Agency in the Bush Administration than Gordon Binder.

Conflicts with the White House

Q: What was your relationship to the White House?

MR. REILLY: The conflicts with the White House on policy matters started early. Budget Director Dick Darman, at the very first informational briefing that I gave on the Clean Air Act, went ballistic and indicated that Ruckelshaus, as EPA Administrator, had brought an acid rain proposal over to the White House in which fish from the Adirondacks were going to be valued at something like $20 a fish. Now Reilly, if anything, has brought over something that is going to cost twice that much, he said.

I said, "There are a lot fewer fish, you should have taken the deal Ruckelshaus offered you." That was the tone of our exchanges for that period. He startled me because his opposition seemed so fundamental. I had rather assumed that - given the President's very public commitments to a Clean Air Act with three parts, an acid rain title, an ozone-smog title, and an air toxics title - we would all get behind that, get in harness, and produce such a bill.

The Budget Director philosophically disagreed with that and didn't hide it. He did not argue as though he considered that we were bound by those promises. He doubted the seriousness of the air pollution problem in the United States. It was a philosophy that [David] Stockman had also espoused - in fact, I think Stockman had greatly influenced Darman.

Governor Sununu, I think, at the beginning had difficulty knowing quite what to make of me. Obviously the Chief of Staff's job is a terrible job. It involves taking responsibility for a very motley crew of people, whom you don't select, who have relationships with the President, political histories with him, who are valuable for one reason or another to constituencies, and making a success out of all that, getting some serious work out of that diversity. Sununu was quick, bright, and perceptive on a number of issues.

He was very helpful to me in the run up to our proposing the Clean Air bill. He asked good questions, knew the utility industry very well, knew pricing policies, and was familiar with the acid rain problem as former Governor of New Hampshire. He paid less attention to other features of the bill and put Roger Porter in to oversee both our development of the legislation and our Congressional shepherding of the law. Porter was very constructive and positive, had endless meetings on the issues - wore people down that way sometimes - and produced with us a very good bill.

I think, looking back on it, it is a model on how public policy in the executive branch ought to be developed. The originating Agency was EPA. That's where the impressive conceptual work was done. The staff that Don Clay had left behind in air had anticipated the need and had prepared themselves very well for the day when clean air would be on the agenda. They had patiently done the analysis, they had all the facts marshaled, and the bill that finally emerged was in large part what they had written. The President was, himself, directly responsible for the alternative fuels part of it. I learned during a visit to Rome with the President how strongly he felt about alternative fuels and the need to promote them.

The pollution rights trading concepts, which are so imaginative and novel in that law, came from a number of sources. It owes a lot, intellectually, to Resources for the Future, work that had been underway there for 20 years. The Environmental Defense Fund had worked with Senators Wirth and Heinz on Project '88 and had advanced those ideas and had played a very important role within the environmental community of giving them legitimacy and credibility in a community that was very deeply suspicious of them. The Council of Economic Advisors, particularly Bob Hahn, were very interested in those approaches and pressed that upon us, and the bill was a vastly stronger bill as a result.

The speed with which we operated we owed to the staff at EPA. They put us in a position to be able to run out so far, so fast. Had we not done that, had we waited until the other agencies were better organized, had their people in place, which by and large they didn't, when we first began moving the Clean Air Act through, I doubt we would have produced as strong a bill. In fact, I used to wonder if ever again in the Bush Administration, had we been given the go-ahead, we could have produced as complex and progressive a piece of legislation as the Clean Air Act. It's one of those things that you get to do, I think, only in the first year, perhaps even the first six months.

We had a very fast start, I remember - partly the consequence of knowing what we wanted to do coming in. We formulated right here in this office the concept - Terry Davies, Dan Beardsley, and I - of having EPA's Science Advisory Board review the major threats to health and ecology and then the degree to which the Agency's programs responded to those problems. We got that started as soon as we got to EPA. We began work immediately on the Clean Air Act.

The Regional Administrator for Denver brought in the Two Forks Dam issue to me at my very first briefing. The Acting Administrator during the hiatus between Administrations was Jack Moore, and during those two weeks between Administrators he began the cancellation process for Alar; and that meant that that was on my plate, so we quickly moved to develop new food safety legislation after that, incorporating the lessons I thought I had learned from that experience. We got the Agriculture Department, thanks to Secretary Clayton Yeutter, interested and supportive of that. The Exxon Valdez oil spill occurred just about five weeks into my term.

That, obviously, took a lot of our time and we then began a follow-up to that. The Oil Pollution Act flowed out of that work and the survey of all the harbors in the United States followed. We also got the President to commit the U.S. to phase-out ozone-depleting chemicals by the year 2000, and we completed a review of Superfund. All in the first six months.

It was an extremely busy, productive, exciting time. There was also the international work. We made a commitment within those few months to embrace a framework convention on climate change - something that Governor Sununu and I worked out late at night in his office after we learned that yet another negative story would appear the next day on the Administration's slowness to appreciate this problem. The President was becoming impatient and concerned and we made that commitment.

On the one hand, one could say that there was conflict, certainly between me and Dick Darman and, not infrequently, between the Chief of Staff, Governor Sununu, and myself. But, I felt it was a productive period and particularly credited Governor Sununu in that phase for accommodating the priority the President had committed to and probably the Governor didn't really sympathize with. He once said to me, "I wouldn't do this, but we're not doing it for me, we work for him." I always respected that about Governor Sununu. I think, despite our frequent encounters and differences of opinion, we respected each other.

I, in fact, felt some affection for Sununu. I used to joke with him, he had a sense of humor. Not many others did joke with him. I recall going to a gas station with him where we were dedicating a new methanol pump with the President. I was concerned with trying to get more publicity for this aspect of our program so I asked the Governor if he could step over so I could pour some methanol on his shoe. I said that it would serve two advantages. One, it would guarantee we got attention to the event - it would put us on the evening news. And two, it would clarify to the country that methanol was, in fact, safe - that is, if his shoe didn't erode off.

Well, that's sort of a rambling answer to your question, but anyway, that characterizes, I think, the first six to nine months of it - at least within the White House itself. There also, I should point out, was a very good early relationship with the President himself. I remember when I learned about the Exxon Valdez accident, I called Governor Sununu and said, "I'm going up there."

He said, "I'll get back to you." He found Sam Skinner on a golf course down in Florida and Sam agreed to cut short his Easter vacation and go up there with me. The Coast Guard, which had legal responsibility under law for the spill, was under him, as Secretary of Transportation. We went up and I can recall having a somewhat different reaction to the experience than Sam did, partly because I think he felt more need to defend the Coast Guard. From our initial overflight I thought the response to the spill was woefully inadequate and ineffective. All the protective booms were broken around the key rivers and streams. The sea had been high the night before I got there. We had been told that a dozen skimmer ships were at work. I only saw two and neither one was working. They weren't suited to a major spill on open, turbulent water.