Ecosystem Services in Lakes

Lakes Ecosystem Services Links

When assessing the condition of lakes, ponds, and reservoirs, these water bodies are often viewed as existing along a continuum from impacted to pristine. This approach is useful for evaluating the overall health of the nation's waters, but is insufficient to adequately evaluate their suitability for alternative, and often conflicting uses. An ecosystem services perspective adds another dimension to lake management.

Ecosystem services as defined by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2003) are: the benefits people obtain from ecosystems (for a review of the concept and additional definitions please see Fisher et al 2009). These services are often critical for life and enhance human well-being. As such they are part of the global commons and are often considered to be free. An ecosystem services perspective is an explicit acknowledgement that nature has value and that the value can be measured and used to support environmental management decisions.

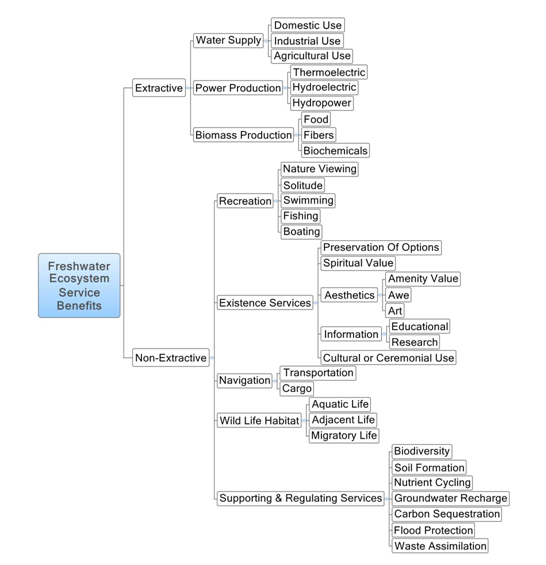

To understand ecosystem services it is useful to evaluate the types of benefits provided by lakes, ponds, and reservoirs. A non-exhaustive list of benefits is presented and more information is available in reviews by Bergstrom et al (1996), Postel & Carpenter (1997), and EPA (2000). These benefits can be separated into: 1) goods and products extracted from lakes and, 2) services that depend on local ecosystem processes or lake infrastructure. In most cases, the ecosystem service benefits closely resemble the designated use categories that states have defined under the Clean Water Act.

Every lake can provide a multitude of ecosystem service benefits simultaneously but the actual output of each will depend on the physical characteristics of the basin and the quantity, quality, and timing of water flow. As anthropogenic influences increase ecosystem services and benefits will be affected. This can present significant challenges to managers interested in maintaining multiple ecosystem service benefits while ensuring overall lake health is maintained.

Within this context however, there are many options open to managers. It should be recognized that not all ecosystem system service benefits can be maximized simultaneously. Decisions will need to be made about which ecosystem services and benefits to emphasize in lake management plans. In doing so, managers need to estimate both the costs of ecosystem services losses as well as the expected gains for ecosystem service increases. For example, clear, weed-free lakes are often highly valued for enhanced property values and contact recreation. However, nutrient reductions, herbicide applications, and shoreline modifications needed to maintain lakes in this condition may adversely affect fish and wildlife habitat and overall water quality. Watershed and lake habitat management strategies need to consider diverse objectives, designated uses, and implications of management decisions on various ecosystem services and benefits tradeoffs.

Some ecosystem service benefits and losses can be quantified in economic terms so they can be included in cost-benefit and benefit tradeoff analyses. Ecosystem services benefits associated with extracted water or biomass can be appraised based on market price or standard economic cost/production function methods. Most of the non-extractivebenefits, however, are more difficult to estimate. For these services, resource economists have developed approaches to valuation based on consumer choices or stated willingness to pay. In stated preference models (also called contingent choice) people are asked to estimate how much they would be willing to pay for ecosystem services or to vote among alternatives that involve cost and benefit choices. Stated preference methods are often used to estimate the value people place on existence services such as knowing a species or habitat exists or will be preserved for future generations.

In contrast to stated preference models, revealed preference models attempt to estimate value by analyzing consumer choices; two common methods are hedonic analysis and the travel cost method. In hedonic studies, regression techniques are used to compare prices for equivalent houses within a local market based on their proximity to areas of aesthetic value such as lakes or among houses on lakes of different water quality. The travel cost method assumes that people are willing to pay more for higher quality recreation experiences, and that the quality of the experience is related to characteristics of the site. By comparing travel cost estimates for different sites researchers can estimate the value of sites and their characteristics. An analysis of the types of valuation studies appropriate for aquatic ecosystem services can be found in Bergstrom et al (1996) and EPA (2000) and Wilson & Carpenter (1999) provide some examples of existing studies.

Caution needs to used be when evaluating economic valuation studies of ecosystem services as methods are controversial, may depend on un-testable assumptions and can yield widely varying estimates. As tools for estimating the relative importance people place on ecosystem services valuation studies can be used to demonstrate that people are willing to pay for services and that choices are often affected by peoples perceptions of environmental quality (e.g., Egan et al 2009). Although subjective, perceptions of quality are often supported by objective measurement. For example, the field crews for the National Lakes Assessment were asked to complete a visual assessment of the disturbance level, trophic state, biotic integrity, aesthetic quality, suitability for swimming, and recreational value of each lake visited. These subjective scores have proven to be good predictors of many of the water quality and physical habitat measures collected. In general, field crews found lakes with greater water clarity (secchi transparency) to be more appealing and more pristine. There was also a high degree of concordance between visually assessed trophic state and trophic status indicators such as nutrient and chlorophyll A concentrations. Subjective measures such as these may be useful as indicators of ecosystem service for ranking benefits and the assessment of tradeoffs. Their study will give insight into how variation in physical, chemical, biological, and landscape characteristics of lakes contribute to perception of environmental quality and ultimately human choices.

References:

Bergstrom, John C., Kevin J. Boyle, Charles A. Job, and Mary Jo Kealy. 1996. Assessing the Economic Benefits of Ground Water for Environmental Policy Decisions. Water Resources Bulletin 32(2):279-291.

Egan, Kevin. J., Joseph A. Herriges, Catherine L. Kling, and John A. Downing. 2009. Valuing Water Quality as a Function of Water Quality Measures. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 91(1): 106-123.

EPA. 2000. A Benefits Assessment of Water Pollution Control Programs Since 1972: Part 1, The Benefits of Point Source Controls for Conventional Pollutants in Rivers and Streams (PDF). (111 pp., 989K)

Fisher, Brendan, R. Kerry Turner, and Paul Morling. 2009. Defining and classifying ecosystem services for decision making." Ecological Economics 68(3): 643-653.

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. 2003. Ecosystems and Human Well-being: A Framework for Assessment. Island Press, Washington. D.C.

Postel, S. and S. Carpenter 1997. Freshwater Ecosystem Services. Nature's Services: Societal Dependence on Natural Ecosystems. G. C. Daily. Washington, D.C., Island Press: 195-214.

Wilson, M. A. and S. R. Carpenter 1999. Economic Valuation of Freshwater Ecosystem Services in the United States: 1971-1997. Ecological Applications 9(3): 772-783.

![[logo] US EPA](../gif/logo_epaseal.gif)