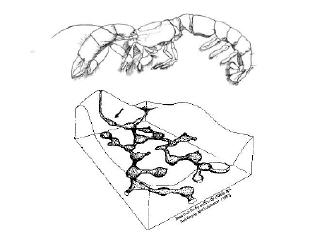

Meet the ghost shrimp (Neotrypaea californiensis). The ghost shrimp lives in mostly sandy sediments in deep burrows typically 50 cm deep but sometimes as deep as one meter!

This is what a typical ghost shrimp burrow looks like. They usually have two openings and multiple chambers.

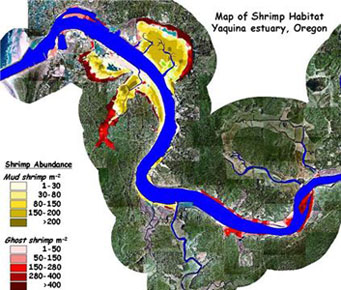

Ghost shrimp density can be very high with as many as 400 per meter squared.

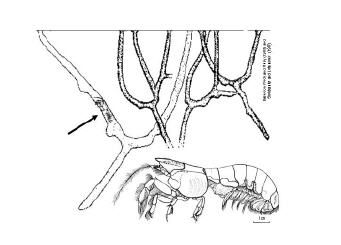

Meet the mud shrimp (Upogebia pugettensis). The mud shrimp lives primarily in muddy sediments. Mud shrimp burrows are usually deeper than ghost shrimp burrows, and can be as deep as one meter.

This is what a typical mud shrimp burrow looks like. They are typically Y-shaped with two or more openings.

Mud shrimp can occur at densities of up to 200 per meter squared.

We know what shrimp burrows look like by pouring resin down into the burrows at low tide.

Then later, after the resin has dried, the cast is excavated.

The shape of the burrow helps scientist understand some of the chemical processes that go on in the sediment.

This map shows the burrowing shrimp habitats for Yaquina Estuary in Oregon; shrimp occupy 70% or more of tide flat area!

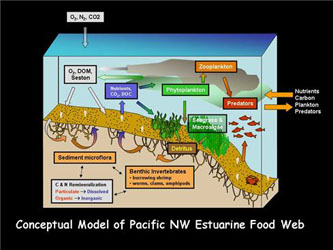

So why are burrowing shrimp important? Burrowing shrimp play important roles in nutrient cycling and other ecosystem services. They also serve as prey for fish, birds and crabs.

They are also harvested by fishermen as bait!

Some oyster farmers use carbaryl pesticide to kill burrowing shrimp on their oyster beds because the sediment the shrimp excavate smothers and buries oysters.

A new exotic species of parasitic isopod (inset picture) threatens the mud shrimp, and may diminish the ecosystem functions supported by the shrimp.

Experiments are set up to measure the effects of burrowing shrimp on nitrogen and carbon cycling

Sediment samples are collected to measure how rapidly the shrimp bury organic matter.

Field experiments were conducted to measure competitive interactions between seagrass and burrowing shrimp.

Hovercraft skim over the soft tide flat sediments and are a great way to get to and from our field sites.

So remember when you look out over an estuary in the Pacific Northest and see all those holes, you are looking at the homes of some very important shrimp species!