Alvin L. Alm: Oral History Interview

Foreword

This publication is the third in a series of oral history interviews with the Environmental Protection Agency's administrators and deputy administrators. The EPA History Program has undertaken this project in order to preserve, distill, and disseminate the main experiences and insights of the men and women who have led the agency. EPA decision-makers and staff, related government entities, the environmental community, scholars, and the general public, can all profit from these recollections.

Separately, each of the interviews will describe the perspectives of particular leaders. Collectively, these reminiscences win illustrate the dynamic nature of EPA's historic mission; the personalities and institutions that have shaped its outlook; the context of the times in which it has operated; and some of the agency's principal achievements and shortcomings.

The techniques used to prepare the EPA oral history series conform to the practices commonly observed by professional historians. The questions, submitted in advance, are broad and open-ended, and the answers are preserved on audio tape. Once transcripts of the recordings are completed, the History Program staff edits the manuscripts for clarity, factual accuracy, and logical progression. The finished manuscripts are then returned to the interviewees, who may alter the text to eliminate errors made during transcription of the tapes, or during the editorial phase of preparation.

A collaborative work such as this incurs a number of debts. Kathy Petruccelli, Director of EPA's Management and Organization Division, sought support for transcription and printing costs. John C. Chamberlin, Director of the Office of Administration, provided the necessary funds. Connie Martin performed invaluable proofreading and logistical services. Finally, Alvin Alm himself must be acknowledged for his candid and insightful reflections on this formative period in EPA history.

Biography

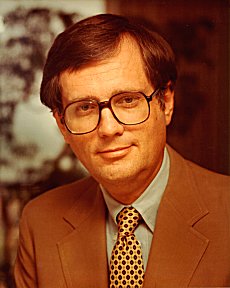

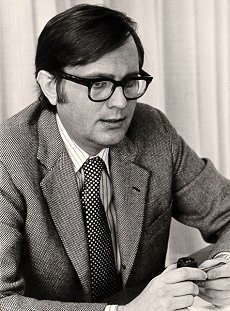

Son of a Swedish immigrant tailor, Al Alm grew up in 1950s Denver. Classically, Alm represents a first generation American rising through the ranks of government and business. Graduating from the University of Denver in 1960, Alm decided, on the advice of a faculty member, to attend the Maxwell Graduate School of Public Administration in Syracuse, New York. Upon graduating, he accepted a position with the Bureau of the Budget as a management intern, where he became involved in the budgeting process for pollution programs scattered throughout the bureaucracy.

In 1970, Alm drew the attention of Russell Train, who asked him to become his staff director at the newly created Council on Environmental Quality. Alm accepted the position, and within three years was asked by William Ruckelshaus, the first EPA Administrator, to become the Assistant Administrator for Planning and Management. Soon after Alm arrived at EPA, Ruckelshaus was asked to become FBI director, and Russell Train became EPA Administrator - renewing the relationship Alm developed with Train at CEQ.

At EPA, Alm oversaw the development of the effluent guideline process, the NPDES permit program, and the creation of financial safeguards for the construction grant program. He devoted attention to building a solid economic-analysis program at EPA, which enabled the agency to minimize the negative economic impact of its regulations.

By the middle 1970s, Alm found himself heavily involved in energy issues. EPA's environmental mandate received less public attention as a result of the rapid increase in energy prices resulting from the OPEC oil embargo of 1973/1974. He was invited to Camp David to help develop the Ford administration's energy policy. This experience, plus his management experience at CEQ and EPA, won him a spot in the Carter administration, first working with James Schlesinger on the Carter energy policy and then as an undersecretary at the newly created Department of Energy.

In 1979, Alm accepted the responsibility of managing Harvard University's energy security program. As an outsider, "ensconced" at Harvard, he watched EPA struggle through its rockiest times to date. When adverse media reports and congressional investigations forced Ronald Reagan's first EPA Administrator Ann Gorsuch to resign, William Ruckelshaus returned to stabilize the agency's credibility.

Ruckelshaus tapped Al Alm to manage the daily affairs of the Agency as Deputy Administrator. Ruckelshaus and Alm served through the remainder of Reagan's first term and then both left the government for the business community. Alm became a senior vice president at Science Applications International Corporation, Inc. in McLean, VA.

Alm played an active role in facilitating the government's campaign to control environmental degradation. With his assistance the Federal government moved from having no effective pollution control system to having a fully functional end-of-pipe one. In so doing, Alm and his colleagues at EPA arrested the widespread degradation of the American environment and laid a foundation for future environmental progress. Alm's career in environmental matters, which he began in the 1960s at BoB, did not end at EPA. Not one to rest on his laurels, Alm outlined his vision for the future of environmental affairs:

"...in recent years, I have seen the change to an entirely new set of paradigms: sustainable development; pollution prevention; use of nontraditional forms of environmental control, like market incentives and information; and integration of environmental concerns into policies across government agencies. We are seeing the change away from command and control, toward more flexible systems, and ultimately toward a decentralized system. It is hard to foresee this transition, but I think it is going to occur, and I would like to continue to be part of it...."

Interview

Early Life and Influences

Q: Mr. Alm, please tell me about your upbringing, family life, and education.

MR. ALM: I grew up in Denver, Colorado. I went to the University of Denver and graduated in 1960. I then went to the Maxwell School, in Syracuse, N.Y. for a master's degree in public administration. I have a daughter, who is a freshman at Wesleyan University.

Q: What was it like growing up in Denver in the '50s and '60s?

MR. ALM: I remember Denver before air pollution. When I lived in Denver, it was kind of an ideal place to be brought up. We were near the mountains. Good weather. A lot of outdoor activities. So it was a very, very pleasant place to grow up.

Q: Did you hunt, fish and those sorts of things?

MR. ALM: Yes, my father was a avid fisherman. We tended to go fishing almost every weekend. I learned how to fly fish, did virtually every kind of fishing all around the mountain areas near Denver. Unfortunately, I never was patient enough to be a good fisherman, but I did enjoy being outdoors.

Q: Were you involved in environmental groups, such as the Izaak Walton League or others?

MR. ALM: Not at that time, no.

Q: What was your father like?

MR. ALM: Well, my father was Swedish American. He was an immigrant tailor.

Q: What are your recollections of him? You said he fished.

MR. ALM: Well, I remember both spending a lot of time with him fishing and visiting the tailor shop he had in downtown Denver. I rather enjoyed just watching how that thing operated. I was probably a real pest at the time.

Q: Did that give you some idea about managing an organization?

MR. ALM: I am not sure it did.

Q: How did your family and friends feel about the environment?

MR. ALM: Well, I think in those days you took it for granted. Again, the first sense that we had in Denver that something was amiss, was when the air pollution got to the point that one no longer had clear views of the mountains. It sort of sneaks up on you and suddenly one day you realize the extent to which, well, we have fouled our own nest with the explosive growth in Denver.

Q: Was there a reaction among the people in Denver against that? Did they recognize what the problem was and try to do something about it?

MR. ALM: Well, I left in 1960. And I think as of that time, at least to my recollection, people accepted it as a natural corollary to progress. As you recall, it was really 1970 when the environmental movement burst forth. I was not in Denver during those 10 years. When I came back in the '70s, there was a great deal of concern. Obviously the Clean Air Act set a very ambitious schedule, reducing three pollutants by 90 percent. So that gave some hope that Denver's air pollution would be corrected. Obviously, even today, considering the meteorological conditions, the high altitude, and the population growth Denver has, there are serious air-pollution problems.

Generational Differences with Regard to Environmental Concern

Q: You mentioned in your previous interview about your daughter at Wesleyan. How do the attitudes of people her age differ from those of people graduating from college in 1960?

MR. ALM: Well, the information they have is incredible. It may not all be accurate, but they certainly have perceptions. I remember when she was a young teenager and I drove her and a bunch of her friends around and I offered to take them to lunch. They had a long debate about which of the fast food franchises was most environmentally desirable. This is something that would have never occurred to us in the '60s. So there is a lot of interest by young adults her age. And I think it is going to have a profound impact on politics, corporate behavior, and on individual consumer decisions over time.

Some people feel that environment is going to go away as an issue as we have to deal with the stark economic realities of a global economy. Historically, there has been a certain amount of waxing and waning of environmental enthusiasm depending on the economic conditions. I believe, however, that the general trend has been positive and that we are nurturing a new generation that has much more knowledge and a different ethic about the relationship of man to the environment. I think it is going to make a political difference, a difference in consumer choices, and a difference within firms. In many firms today, you see some of the younger people being proponents for the environment within their companies.

Q: You mentioned a different ethic that young people have. How would you define that ethic?

MR. ALM: It is an ethic that concerns itself not only with obvious forms of pollution, but concerns itself with use of materials and the way we dispose of residuals in our society. There is a great deal of interest in recycling and purchasing "green" goods that don't have adverse environmental effects. The ethic results in a much more personal involvement with doing something about the environment rather then merely supporting governmental actions or contributing to environmental causes.

Q: Where do you think the roots of that have...?

MR. ALM: That is a good question. Certainly in 1970, environmental quality became a big political issue. With Earth Day acting as a national catharsis, releasing pent up enthusiasm and concern over the issue. Environmental groups grew rapidly and became very active. Over time, environmental concerns seeped into the educational system and received constant press attention. By the late 1980s, there was a recognition that environmental problems were global in nature. In 1992, we saw the largest concentration of nations in the history of the world at Rio [1992 UNCED meeting]. That was big news. All these things tend to be reenforcing.

These changes are having a large impact on industry, fundamentally different than in the early days. In the early 1970s, industry, manufacturing industry to a great extent, opposed many of the environmental laws. By the late 1970s and 1980s, industry learned to live with regulations, although not always with great enthusiasm.

Today, you see many companies now trying to be very proactive by establishing their own pollution prevention programs. For example, some of the big forest products, chemical and petroleum companies are taking credit for their contributions to the environment. Many believe environmental progress can represent a competitive advantage.

A couple of years ago, Dow Chemical had a cover on its annual report that said that no issue was more important to the future of the company than the environment. Such a statement would never have been made a decade ago.

Government Career

Q: Why did you go into government service?

MR. ALM: Well, I was always interested in government and politics. Like a lot of young people I wasn't quite sure what I was going to do with my life, so I planned to go to law school. One of my professors told me about a scholarship that was available at the Maxwell Graduate School of Public Administration in Syracuse. He suggested that I apply for it; and, I thought, why not? I was awarded the scholarship and decided that I would go the Maxwell School for a year and then get a law degree. During the year at the Maxwell School, I took the management intern exam for the federal government, which I passed.

Based on a series of interviews, I had a number of exciting job opportunities. That was a time in our nation's history where government service was very highly regarded. Most graduating students were interested in public service of one kind or another. Very different than say the '80s, where the opposite was true. So it was very exciting. And one night I just sat down and decided: am I going to law school or am I going take one of these jobs. I decided to take a position as a management intern with the Federal Government. And ever since then, my life has been a series of new challenges and opportunities.

Q: How did you come to have an interest in environmental matters?

MR. ALM: Well, in terms of the environment itself, obviously, growing up in Colorado, made me conscious of the beauty of nature. Professionally, I got involved with environmental programs at the Bureau of the Budget, where I was the principal budget examiner for the water pollution program. I really got very interested in the pollution control programs. So in 1970, when CEQ was created, I was asked by Russell Train to come over and play a senior role. And clearly it was what I wanted to do in terms of dealing with programs, and what I considered of great importance to the country.

Mentors

Q: Who would you say were the most important persons in your life? Who were your mentors, people who influenced the direction of your life?

MR. ALM: I have had many really outstanding bosses. Kermit Gordon and Charley Schultze were my bosses at the Bureau of the Budget. Russell Train, whom I worked for at CEQ and EPA, significantly influenced my career. Jim Schlesinger was my boss at the Department of Energy and a good friend. I worked with Bill Ruckelshaus twice while he was at EPA, although only once directly. In my public life, all these people had a major influence on me, and I learned a lot from them.

Q: What did you learn from them?

MR. ALM: I learned how to make decisions in a political environment. Generally, these people were good decision-makers. They are all very honest people. They all had good senses of humor, and they were all very bright. I believe honesty, intelligence and a sense of humor are the three most important characteristics for a public official to possess.

Russell Train

Q: How would you characterize your relationship with Russell Train?

MR. ALM: I have known Russ since 1969. I initially met him early on in the Nixon Administration when he was nominated to be the Under Secretary [of the Interior]. We worked on the oil-pollution legislation. We hit it off well from the very beginning. Afterwards, I dealt with him from time to time when he was Undersecretary of the Interior and I was at the Bureau of the Budget. He asked me to join his staff at Interior but by the time I was ready to move he was nominated to become Chairman of the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ). He asked me to come over and join him at CEQ in a senior position.

So I worked for Russ for about three and a half years at CEQ as staff director. I then had the opportunity to go over to EPA to work for him as Assistant Administrator for Planning and Management. I have never worked for anybody as long as Russ. It was really very enjoyable, and professionally rewarding. He is a true gentleman in every respect, a person for which I have the highest respect.

Comparison of Train and Ruckelshaus

Q: How did his style and interests differ from those of Ruckelshaus?

MR. ALM: They have an awful lot of common characteristics. Both of them are very shrewd judges of people. They are both extremely bright. Both are lawyers. Both have great senses of humor. They tend to do very well under pressure. For both of them the more pressure they get under, the more they can laugh at themselves in the situation. They are both very astute politically. I mean this in the good sense of understanding what is possible and getting it done. Finally, they have a great ability to delegate. Both Bill and Russ Train gave me a lot of responsibility. And yet they stayed on top of the important issues. So they are good managers in that sense.

Q: Did they have different interests?

MR. ALM: Well, Russ is most interested in wildlife kinds of issues. They interested him much more viscerally than many of the pollution issues. Not that pollution issues didn't interest him.

But, Ruckelshaus, at least in the second term, which was when I worked for him, was always grappling with the process of decision-making and how the public could be informed about choices. He saw his role as that of the chief environmental educator.

Train had the good fortune of being at EPA during the years when most was accomplished. During the first three and a half years, EPA was mainly getting its act together and getting the programs started to implement the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act of 1972. During the '74 through '77 period, very measurable improvements in air and water pollution occurred from EPA implementation of this legislation.

Arrival at EPA

Q: How did you arrive at EPA?

MR. ALM: After the election in 1972, the job as Assistant Administrator for Planning and Management at EPA came open. At the time, I was the staff director for the Council on Environmental Quality. Bill Ruckelshaus and I talked about it, and he indicated that I would be his choice for the job. Ultimately, I was nominated to be the Assistant Administrator for Planning and Management. This was in 1973, just about twenty years ago.

Q: Do you think Russell Train had anything to do with your EPA appointment? Did he recognize you as a talent, and recommend you to Bill Ruckelshaus, or...?

MR. ALM: No. At that point in time, he actually wanted me to stay at CEQ. It is kind of ironic that I went over, and then, through a series of events, Bill wound up as the head of the FBI, and then deputy attorney general. Russell Train then became EPA Administrator. I like to think that I brought some good people over to EPA. (laughter)

Expectations of EPA in Mid-1970s

Q: When you first became Assistant Administrator for Planning and Management, what were your personal expectations there, and what ideas did you bring to the agency?

MR. ALM: I had been involved with economic analysis issues. So, I was interested in strengthening EPA's ability to conduct economic analysis. I thought this was going to be a big issue within the administration and felt that if EPA had a good capability, it would fare much, much better in its relationships with OMB and the White House. Initially, that was something that I was very interested in.

I think when you actually take on a job like this, you begin to get a better sense of the issues. Early in my tenure as Assistant Administrator, EPA was implementing the Clean Water Act. I spent a lot of time on Water Act issues: the development of the effluent guideline process, the NPDES permit program, and financial safeguards for the construction grant program, which at one time was the biggest public works program in the country.

I also got involved with Clean Air Act issues - with what became the rules for prevention of significant deterioration. I also helped develop the administration's position on what became the 1977 amendments to the Clean Air Act.

Toward the end of my tenure as Assistant Administrator, I was involved with reorganizing the agency so that it could implement the Safe Drinking Water Act program, the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), and the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA).

EPA Style in Mid-1970s

Q: What did EPA employees face in the 1970s in terms of taking a new piece of legislation and implementing it? What difficulties did they face that might have slowed down processes?

MR. ALM: There were not that many difficulties other than just the typical difficulties of bringing on new people, training them, etc. But, then, there was a newness, a freshness. The Agency was not as mired down in bureaucracy. And because of this, we were, for example, able to issue all the water pollution control permits in a few years. There was a realization at that time that progress was really critical and perfection could be the enemy of progress. The theory we had on the issuance of the water permits was, "let's get them issued fast, let's get the abatement underway, and then we will come back later and fix the permits that weren't so good." Well, it turned out that the rather rough and ready approach that was used, "good engineering practice," tamed out to be pretty good and most of those permits didn't have to be dramatically altered.

In the Superfund program today, for a lot of legalistic, political and bureaucratic reasons, the attempt at perfection drives up the cost and subjects people to unnecessary hassles. It is just a different world.

EPA and OMB

Q: Based on your experience at the Office of Management and Budget, what do you think the historic nature of the EPA/OMB relationship is, and how do you think that relationship could be improved?

MR. ALM: In general, that relationship has been a pretty uneasy one. And one of the problems has been the OMB regulatory review process. Within it, junior people have a lot of power, particularly to delay decision-making. It creates a lot of tension between OMB and EPA. Perhaps an expedited process for reaching decisions between EPA and OMB and the White House would help. During the time I was there, the problem was that you never really knew where things were. It just seemed like the issues would wind up in OMB, and unless there was some sort of real pressure, like a court deadline, it was very hard to break them loose.

Management and Budget Organization

Q: During your tenure, the planning and budgeting functions were consolidated into one AA'ship. What do you think the strengths and weaknesses of this arrangement were, and what is your perspective on the evolution of these functions into two AA'ships?

MR. ALM: The strength of a consolidated planning and budgeting AA'ship was that it almost created a number three person in the agency. With the right kind of person, you could get a lot of things done - in the areas of administration, resource management, planning and evaluation. However, the scope of duties under such an organization is simply too big for one Assistant Administrator. It really makes sense to break it into two AA'ships. One persistent issue has been where the budgetary function should be. Should it be in administration, as it is now, or should it be in the policy shop? That debate, I assume, will go on for a long time.

Functional Organization

Q: One of EPA's early goals was to mount a cross-media attack on pollution by organizing the agency functionally. Why did the agency not continue to pursue that goal? In hindsight, was that the right decision?

MR. ALM: EPA's major legislative enactments are all based on media - the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act, et cetera. Therefore, EPA's programs and organization tend to be based very heavily on media. Some of EPA's offices are functional, e.g. Research and Development, Enforcement and Compliance Monitoring and the General Counsel's office. But EPA has always retained media-based programs to mirror legislative authorities.

There has been talk about organizing differently, but I don't expect any fundamental reorganization, unless Congress provides EPA greater latitude in operating its programs. As we stand now, different program deadlines are provided specifically in each major statute. There is no broad legislation that requires you to have an environmental permit by such-and-such a date. Instead, the Clean Air Act sets requirements and deadlines for air emissions and the Clean Water Act sets different requirements and deadlines for water effluents. From a management point of view, organizing functionally in that kind of legislative environment becomes very, very difficult.

Economic Analysis Capability

Q: In his oral history interview, Russell Train stated that the most important thing you did, during his administration, was build a strong economic-analysis capability, which he claimed was the best in government. What is your reaction to his claim?

MR. ALM: I think we certainly had the best economic analysis shop in government. I don't think there is any doubt about that.

Q: What was your role in building that program?

MR. ALM: There was a very good staff in place when I got there. I brought on a new office director, Paul Brands, and some key people. And we were continually recruiting. But we had really outstanding people there, at the time - Roy Gamse, Jim Janis, and others. We brought together some of the best people and put them into positions of responsibility.

Q: These were people both inside and outside the agency?

MR. ALM: Yes. But a good deal of the people in that shop, in the planning and evaluation part of the organization, were there when I got there.

Q: Mr. Train went on to say that he believed that the effectiveness of the economic-analysis program had declined over the years. What is your feeling about that?

MR. ALM: I have heard that, but I am not sure it is true. The office of OPPE is many, many times larger now than when I was there, and they have got some very talented people. So, my sense is that the staff is very capable now. I would have a hard time really comparing the relative quality between the staff when I was there and the present staff.

Looking back nostalgically, some of the people really made outstanding contributions, like Walt Barber, Roy Gamse, Jim Janis, and many others. But, I suspect some of the young people coming up now will also make major contributions.

Q: What examples can you think of that really illustrate the quality of EPA's economic capability in the mid-1970s? What anecdotes can you remember that might illustrate that?

MR. ALM: We were required by the Clean Water Act to issue effluent guidelines for water pollution. Besides understanding what was technically feasible, it was very important to understand economic impacts. During those early years of the environmental program, we did not wish to cause unnecessary economic dislocation. We also wanted to have good data on job losses resulting from environmental regulation. The economic analysis performed resulted in reducing adverse impacts and hence not undermining the water-pollution program. We did various studies on the impact of environmental controls on entire industries at that time. We also reviewed the impacts of major regulations focusing heavily on cost effectiveness, for example, looking at what is the cost per ton of pollutant removed.

Q: How did that differ from what CEQ was doing in terms of looking at cost benefits of regulations?

MR. ALM: Well, CEQ did not evaluate individual regulations. When I was there, CEQ did the initial evaluation of the economic impact of pollution control in industry. But over time that function really flowed over to EPA.

EPA and Energy Crisis

Q: During your tenure at EPA, as an Assistant Administrator, the energy crisis had a great impact on the American people and the Federal Government. How did that crisis affect the agency and your work there?

MR. ALM: Well, I don't think it affected us profoundly. In 1973/1974, Arab oil embargo required us to pay attention to coal use. EPA took some leadership in the coal conversion program attempting to help the Federal Energy Administration shift private utility power plants from oil to coal. Other than that, it did not greatly change our life at EPA.

Q: Do you think EPA changed the life of the nation during that period of time?

MR. ALM: No. I do not think so.

It depends on what you mean, "that period of time." In 1973/1974, the U.S. experienced gasoline lines and severe economic shock. The Iranian shortfall in 1978/79 caused similar problems. Energy was most prominently a public policy problem from 1973-1981. It could become a major problem in the future as U.S. imports continue to rise and domestic oil production falls.

At that time in EPA, we developed an energy policy capability. I brought over a fellow named Walt Barber from OMB to run this program. We worked to develop various government positions on energy conservation. We were in favor of legislation creating the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards. We supported the Ford Energy Plan, particularly natural gas price deregulation and conservation measures. I was personally invited to the Camp David planning meeting that led to the development of the Ford Energy Plan.

In 1977, with the beginning of the Carter administration, people felt that the nation was facing a major energy problem. I went to work with Jim Schlesinger in the White House to oversee the development of Carter's energy program. The perspectives I had gained at EPA played a role in the kind of energy plan we put together.

Q: What perspectives did you gain at EPA that affected the energy policies that you helped draft for the Ford and Carter Administrations?

MR. ALM: Well, what I gained in being at CEQ and in EPA, first of all, was the ability to know how to put something like this together and to relate one piece of a system to another. Obviously, you bring to anything certainly an amount of sensitivity. When I was at EPA, I had concluded that the country would be better off both environmentally and economically if oil and gas prices were decontrolled. And we were actually supportive of decontrolling energy prices. As a historical aside, I am the only person who has participated in the development of the Ford Energy Policy at Camp David and later played a major role with the Carter energy plan.

Jimmy Carter came in as a pro-environmental president, so there was no doubt that from the very beginning he wanted an energy policy that was protective of the environment. And considering my experience at EPA and my other experiences I think I had a general idea how one could work in environmental considerations into an energy plan.

Significant Issues at EPA in 1970s

Q: In your mind, what were the most significant issues the agency faced during your time as an AA?

MR. ALM: First of all, EPA implemented the Clean Water Act. I think the agency did a great job getting out most of the NPDES permits in a relatively short period of time. It made a real contribution to the water-pollution-abatement problem.

A second significant issue the agency faced was developing and implementing a waste-treatment-grant program, over $20 billion worth of expenditures, without scandal. Our success at that was really remarkable. We worked very hard to assure the fiscal integrity of that program.

Finally, I think the Clean Air Act, what became the Clean Air Act amendments, was a significant contribution the agency made during my tenure there.

Achievements at EPA

Q: What are the lasting achievements of your first four years at EPA?

MR. ALM: I think I brought in and nurtured some very, very good people, who have subsequently taken all kinds of leadership positions, both in the government and in the private sector.

Carter Administration's EPA

Q: The Burford administration's management, those who came in after President Carter's EPA Administrator Douglas Costle left, said that EPA had been unnecessarily slow in promulgating regulations, not issuing permits in a timely manner, and that sort of thing. Was that something that was endemic to the big crunch of implementing legislation or was there something at EPA from the time Train left to the time...?

MR. ALM: The Carter Years are very interesting. For some reason, during that time regulatory activity was much lower. There were a couple of big regulations issued then. One was the New Source Performance Standards for electric utility boilers. That was a very big issue. There was also the original RCRA regulations that were issued in draft during the Carter administration. But, the regulatory action was down, because of circumstances. But, the Carter people did have to begin the implementation of RCRA and TSCA. These laws had really just enacted at the end of the Train era.

DOE and Harvard Energy Security Program

Q: Between 1977 and 1983, you were the Assistant Secretary for Policy and Evaluation, in the Department of Energy; and later, became the director of the Harvard energy security program. How did those experiences change your perspective on environmental affairs?

MR. ALM: Well, they really indicated to me how inexplicably intertwined the environment and energy really are. Many of, in fact, most of the air pollution problems result from fuel and energy production. Hence, it is clear to me that in the U.S., energy and environmental policy have to be congruent. Only then will we be successful in reconciling them with each other. That is even more true when you go to places like Central Europe, where energy policy really is the predominant force in determining environmental conditions.

Q: How did your experience at DOE and Harvard change the way you implemented EPA's mission when you returned in '83?

MR. ALM: Well, when I ran a research program at Harvard and I found it so frustrating to get anything organized or even to hold a meeting in which you would have all the people there at any particular time. These frustrations led me to be very, very conscious of efficiently using people's time. And I made a rule, which I almost always kept at EPA, that meetings would begin and end on time. That is really important because otherwise you are just wasting a lot of people's time. At the beginning people had been used to a different kind of pattern and I held up a couple of meetings until the latecomers arrived, reminding them that they were wasting the time of all their colleagues.

Return to EPA

Q: What events led to your return to EPA as Deputy Administrator in 1983?

MR. ALM: While I was ensconced at Harvard University, running the energy security program, I remember reading in the newspaper about the problems at EPA. They made their way all the way to "Doonesbury." I had heard a rumor that Ruckelshaus was going to be the next administrator, and I confidently told the source of that rumor that it would never happen - people do not come back to the same position. But, Bill did come back and he asked me if I would come on board as his deputy. I said I would.

I was surprised at this turn of events. At that point in time, I did not think that I would be coming back to government. But I felt the agency was really in need of some help, and if Bill believed I was the right person, I was willing to do it.

EPA Mood

Q: When you returned to Washington, what was the mood at EPA? Did it surprise you?

MR. ALM: After Bill had come back, the mood was pretty upbeat. I came back as kind of a known commodity, as did Jim Barnes, Howard Messner, Jack Raven and Phil Angel.

What always concerned me was that the mood was too upbeat - that expectations were going to be very high. When expectations get high like that, there is a great chance that they become unfulfilled, and people become very cynical. So I told Bill that I thought we ought to move pretty quickly, and we did. We made virtually all of our main appointments within a couple of months. We had ten task forces going almost immediately - in the first full week I was there.

So we moved quickly and got a lot of people working. I thought it was very important to initiate a lot of action and involve a lot of people. And that is what we did. In those ten task forces, with God only knows how many people on each task force, we were dealing with many hundreds of people who were now participating in revitalizing the agency.

Q: Would you consider those the measures you took to restore faith in the agency, among both staff and outsiders, or was there something more that you did?

MR. ALM: In terms of instilling faith in the agency, I think being honest and open was important. I think Ruckelshaus certainly created that image of honesty. But another part of building faith was creating confidence that we were getting work done. The one area that was being most questioned was the enforcement record.

Bill and I thought that we would just come back, and it would turn around. But actually, over a period of time, people had gotten used to a pattern in which enforcement was not used as a compliance tool that often. I certainly spent a lot of time pushing to reach a point I would call the enforcement threshold - a point at which there is a pervasive sense that it pays to comply. I think that is very, very important, because I am convinced that most industries want to comply, and want to be in a position where, from a competitive point of view, compliance is not a negative factor.

In order to ensure that everybody could comply, without suffering major competitive disadvantages, we needed a strong enforcement program - strong enough to convince industry that there was a very high likelihood that noncompliance would be the subject of enforcement action.

Reinvigorating Enforcement Activity

Q: What steps did you take to try to reach that enforcement threshold?

MR. ALM: I set up a management system to track the activities and outputs of the agency. One of the things that I tracked was compliance with the laws. It worked like this: we identified all the noncompliers, at the beginning of any year, and then set goals for what we expected to get the noncompliance rate down to by the end of the period. I would go around to all the regions quarterly and we would go over this measure, and others, in order to get a sense of how well we were doing in our effort to bring people into compliance.

Q: So the people in the field were doing a good job monitoring noncompliance even though the agency had gotten lax in its enforcement effort? You knew who was in compliance and who was not?

MR. ALM: Yes, we either knew or were able to find out. Once we set clear goals, the enforcement rate did pick up. Ultimately, we reached levels as high as any time in the history of the agency.

Business and Environmental Compliance

Q: You said a moment ago that you thought that businesses and industries really wanted to comply with environmental regulation. That flies in the face of the big business, anti-environment stereotype. Why do you have the impression that most industry wants to comply?

MR. ALM: Several things are happening to encourage this. One is that large firms have a big stake in their corporate image. Secondly, environmental liabilities have some, and it is probably modest right now, impact on the stock price. But they may have a larger one in the future. They can certainly have an adverse impact on the bottom line. Another thing - some of the younger managers are environmentally inclined - in the companies. We have seen a tremendous turnaround in the attitudes of chemical and petroleum companies. Just look at their institutional advertising!

Being in business myself, my sense is that businesses would like to comply, but, obviously, they do not want to be at a competitive disadvantage. That is why it is very important, domestically, to have an enforcement threshold. That same problem is hitting us with the North American Free Trade Agreement. We have to develop the ability to make sure that environmental standards are similar throughout North America so that there are no competitive disadvantages.

Relationship with Ruckelshaus

Q: How would you characterize your working, as well as your personal, relationship with Bill Ruckelshaus?

MR. ALM: I think it was really excellent. When I came on board, I told him that I would like to meet with him most mornings of the week. I think we decided on three days, three mornings, a week, and to have lunch together one day a week. We held to that pattern and it was really invaluable. We stayed in communication with one another. There is a real tendency among agency heads and deputies to not get along. There are more occasions when they do not get along than when they do get along. I think Bill and I had a particularly good relationship. We had a very similar sense of humor. We had very similar views of people and events. It was a very friendly kind of relationship, a very nice personal relationship, and a very good professional relationship.

Reasons for Not Completely Reorganizing Agency in 1983

Q: Why did you and Ruckelshaus not reorganize the agency's structure and reverse some of the Burford administration's decisions, such as the decentralization of the enforcement structure, on your return in 1984?

MR. ALM: People are still arguing about the organization of the agency's functions today. Some people want to centralize the enforcement function. Others want to centralize the media activities. For us, with about an eighteen-month horizon, it would have been madness, with everything else we were trying to do, to try to conduct a major reorganization. If that were to happen, it should have happened at the beginning of the Thomas era, or the Reilly era. Incidentally, GAO concluded that there was no inherent advantage in either a combined or media-related enforcement structure.

In terms of other decisions, we changed the direction of many of the programs - including the Superfund program, which was under a lot of criticism. As I explained previously, we also beefed up the enforcement effort. I would say that, generally, we did not make changes for change's sake, but there were a lot of changes. Reorganizing the enforcement function has not been addressed by any subsequent administrator, either. We'll see whether Carol Browner addresses it. [Subsequent to this interview, Carol Browner decided to combine the enforcement activities in one office.]

Thoughts on Agency's Organizational Structure

Q: If you were asked to tackle the agency's organizational structure, in 1993, what changes would you make?

MR. ALM: You know, I am not sure, I am honestly not sure. When I was in the agency, I started what became the policy of the agency to rotate people around - people would move from office to office, and from headquarters to the region, and from the region to the states. I think it is very important that, even though the laws are written the way they are, we begin to implement environmental programs as a totality. Because, in an ecosystem, or in any particular local area, you don't have just air pollution or just water pollution. You normally have a range of environmental insults.

I mention this, because I think you can begin to get this concept through to people, regardless of organization. I don't know of any nifty way to organize, that would both be operationally sound and begin to really integrate environmentally in a broader way. I have not thought about it for some time, and maybe if I really had the responsibility, I would come up with something. But I do think it is really important, very important, that people in the environmental field move around. You should not have people that are just water experts, or just air experts. They really need to have a broader concept of the environment.

Role as Deputy Administrator

Q: Environmental Forum suggested that you were the most influential Deputy Administrator the agency had ever had. What did you do different from your predecessors or successors?

MR. ALM: Well, I do not know if that is true, but I think that I came in with a pretty clear idea of what needed to be done in the agency. I had some ideas about how to develop the management structure to do it. Bill Ruckelshaus was really enjoyable to work for and gave me the flexibility to operate. We took great pains to prevent our staff shopping between us for decisions. I had excellent relationships with the career staff, and played a role in the appointment of many of the political appointees, and knew the others. It was a good team effort. Just having a supportive boss, a knowledge of the programs of the agency, and personal contacts with the people - all those things helped.

Mission vs. Management Culture

Q: In recent years, the agency has come under severe criticism, from Congress and inside the agency, about its mission versus management culture. What is your assessment of this criticism?

MR. ALM: In my opinion, the management challenge for an institution - whether a business or public sector agency - is to achieve its mission. To consider mission separate from management is doublespeak.

I remember once hearing a very, very funny British spoof, and it went along the lines of these guys who had this model hospital, but it did not have any patients. Somebody asked them why their model hospital didn't have any patients. They said, "we can't have perfect systems if we have patients. The patients will screw up the flow." So you can have perfect systems, and still not accomplish a mission.

I think that management is important. I think that, in government, there is never enough time and attention paid to management. There is generally a belief that deputy administrators, who are really chief operating officers of very large entities - EPA is a $6 billion, 17,000-person entity - can be handled by people with no previous management experience. To me, this is like bringing in a brain surgeon to fix your plumbing.

That is a source of the problems. A lot of an agency's management requirements really are at the political, executive level. Many equate management to administration of sub-systems, such as facilities or contracts. To me, management means the focusing of the organization's resources toward achieving a set of goals. These goals are all designed to achieve the organization's mission. The management really comes together, at the Deputy Administrator level, and I think that position should really be filled by somebody who has management ability.

Science at EPA

Q: Administrator Ruckelshaus and others called for increasing the role of science in the decision-making process. How would you characterize the role science and scientists played in policy making, and how had that really changed, between the mid-Seventies, and the early Eighties?

MR. ALM: Bill initially called for greater use of risk assessment and for separating risk assessment from risk management. I believe he was generally successful in inculcating these values in the agency.

I think the agency does a pretty good job of working science into the decision-making process. The agency has a science advisory board and most of the regulations have a substantial amount of technical content behind them.

One of the problems, though, is that many of the statutes that EPA administers leave no room for scientific judgments. As a result, some things are done that may or may not make scientific sense. Some of the statutes presently require that certain regulatory actions take place, without regard to any knowledge about the risks involved. That sort of thing does not make a lot of scientific sense. So I think that, if there is any mismatch between science and what the agency does, it results from statutory enactments, many of which do not leave a lot of room for scientific matters.

Congress, White House, Courts, Environmentalists and Industry

Q: How would you characterize the agency's relationship with Congress? Do you remember any anecdotes that illustrate the agency's, or your own, relationship with Congress or congressional staff?

MR. ALM: I think it was generally okay. EPA goes before a lot of different committees. It has a few supporters and many detractors. It is tough sometimes, because there are obviously a lot of negative issues involving EPA. My sense, though, is that the appropriations committees have been generally supportive, at least when I was there. The authorizing committees, certainly the Senate Environment and Public Works Committees, were also supportive. Actually, the Congressional relationships were generally pretty good. I am not sure that is still the case.

I remember once [as AA for Policy and Planning] I had temporarily experimented with the use of an auto pen. And one day I got a call from Train, who said that our appropriations bill was held up because of some letter I sent. I traced it and found a letter had been written and autopenned back to a member of the Appropriations Committee under my signature. The letter was a peremptory brush off. That was the end of my use of the auto pen as an experiment. Needless to say, I solved that problem quickly.

Q: I guess so! You said that congressional committees such as the Senate Environmental Public Works Committee were pretty supportive of EPA, why do you say that? What do you remember about how they were supportive as opposed to perhaps other committees or as opposed to what they could have been?

MR. ALM: Well, they were supportive in the sense that they were always trying to help with resources and the like. They would play whatever role they could with the appropriations committees. And I suspect they were supportive of EPA vis-a-vis the OMB on those kinds of issues. You know, from a day-to-day point of view it used to be a pain in the neck, being dragged up by staff members and the like. But, I think overall it was a relationship that was helpful to the agency.

Q: What do you recall about EPA's relationships with its other constituents - the White House, the courts and environmental groups and industries? What anecdotes can you recall that might illustrate those?

MR. ALM: The White House relationships were somewhat difficult; I include OMB in the White House equation. Certainly, I think Bill Ruckelshaus had a hard time dealing with OMB; and, certain parts of the White House were not that supportive, other parts were. Jim Baker and some others were supportive, some were neutral. It was a difficult set of relationships in my opinion. Russ Train had a fairly good relationship with John Ehrlichman and very friendly relationships with the Ford White House.

The Courts. My feeling about the courts is not so much the feeling of what happened at EPA at the time, but what l see in more recent periods. The courts do an awful lot of second guessing of administrative agencies' decisions. I was recently involved with a Carnegie Commission Panel, which had a number of distinguished jurists. We talked about the relationship of courts and what kind of technical information they need or how they can make these decisions. All I can say is it is a real quandary when the courts begin to try and understand the technical data outside their areas of expertise. I remind lawyers how they would feel about people practicing law without legal standing. They run into the same problems when they begin to interpret science.

Environmental groups. I have had many very good personal relationships with people in environmental groups, many of whom sue the agency or criticize our actions. I never took these things personally or seriously. I remember being in various debates with people from environmental groups and they would always say "Al is a good guy, but he can't get anything done in the administration." The relationships with environmental groups were generally positive. And I still consider a lot of the people in the movement friends.

Industry. I believe manufacturing firms have come a long way for a whole bunch of reasons. Many firms are really making strong efforts to not only comply but to be proactive - to go beyond mere compliance. Industry is entering into voluntary programs to reduce pollution for a whole bunch of reasons: liability and concern in some circles about even criminal liability. They are also doing it because of concern about how they look to their customers and community. I dare say there are people in the firms that really believe that there is an obligation. Finally, I think many CEOs see an inevitable environmental transition and believe that being on top of the environmental issue will be a key element in long term competitiveness. And I think they are right.

Q: Some critics of EPA have suggested that there is a revolving door in the agency. They claim that the ease with which top officials move between corporate and government positions has detracted from the agency s credibility, and hampered its effectiveness. They have made this point with regard to some of Mr. Ruckelshaus's actions after he returned to the agency after having been with Weyerhaeuser. What is your assessment of this idea?

MR. ALM: I have never heard that criticism. But, I guess there are not very many people that have been out of the agency, who have come back. The only two I know of are Bill and myself. And, certainly, at the time, people made entreaties to our patriotism and vanity to come back. I don't think anybody was looking for any gain. I am sure that Bill lost a small fortune, coming back, and for me it was certainly most disadvantageous financially for me to come back. Still, I think that both of us felt that the agency was in a critical position. I can only speak for myself, but when you are asked, under those conditions, to serve, you probably ought to be willing to do so.

I think this revolving door syndrome is a uniquely American phenomenon. I think, on the contrary, that it would be very desirable to have people moving from industry to government, and to state governments, too. The more of that kind of movement, the better. Obviously, you need to be very careful of the direct conflicts of interest, but I don't think that a person's service in the private sector should be a barrier to their government service. It should be, in many cases, something that could be usefully tapped.

Ethics

Q: What impact do you think President Clinton's new ethics rules will have on EPA officials, and on senior industry officials, and what do you think the overall effect will be on environmental progress?

MR. ALM: I do not know. I assume, seeing the number of people that are coming into government, that people feel that there is some way that they could earn a living after leaving their government service. Nevertheless, I am aware of a number of people who felt they could not assume a government position because of the conflict of interest requirements of the Clinton Administration.

I think strong ethical rules are a good idea. I do not think anybody should ever use government to promote their own personal interests. I have always thought that the biggest ethical challenge was how somebody leaves the government and winds up in the private sector. That issue is a difficult ethical issue, that probably needs someone to really look into it - to think through how people can exit the government without being involved with people who might affect their situation after they leave government.

Achievements and Lessons Learned in the 1980s

Q: During the period between 1983 and 1985, what were the agency's most important achievements?

MR. ALM: Well, I think we turned the ship around, in terms of public credibility. We certainly increased enforcement. We implemented a groundwater policy. We made the decision to get lead almost completely out of gasoline. We got an awful lot done. We established an Office of Human Resources. We started the whole notion of staff rotation within the agency. We also set up strong management systems that were used many years afterward. And we changed many of our decision processes.

Q: What are the most important lessons current agency leaders could learn from your period?

MR. ALM: I think the positive ones are that you must choose people that have some experience to get a head start on the problems. Clearly, creating trust and providing leadership to the bureaucracy is critical. People that do not understand this, who create a gap between the professional bureaucracy and the political appointees, will pay very dearly. I also think candor in public programs pays off. Bill was very, very candid about the limitations of what could be done, and what could not be done. I think, overall, people respected that.

Q: Any negative lessons?

MR. ALM: Frankly, I can't think of any at this time.

Challenges for the 1990s

Q: What are the most significant challenges facing the agency in the 1990s, substantively, politically, and managerially?

MR. ALM: Well, one of the biggest challenges is to speed up agency processes. Promulgating a regulation now takes over four years, and sometimes up to eight years.

A second challenge is to transition into results-oriented management. In the early years, we were very results-oriented - especially in the water program and the air program. That orientation is responsible for the big changes in those areas. In those media, we are now dealing with the intractable kinds of problems - nonpoint sources, various sources for air pollution, etc. These really require a different kind of approach.

We are now at the point where we have so many environmental problems that we need to begin to deal with them geographically. That means that EPA is going to have to decentralize in some creative ways. For instance, we have technology, through geographical information systems, to plot all the environmental problems, by state, or county, or whatever. So we need to begin the process of thinking through, and transitioning to, an entirely different management structure for the environment. I am convinced that it is going to happen someday. What we have, right now, is going to be unrecognizable. It may take a long time, but one needs to plan for that transition and to assist it.

Career Summary

Q: How would you sum up your career in the environmental field?

MR. ALM: I do not think it is over, yet. (laughter) It has been an exciting period. I started in the pre-Earth Day period - in 1966. In those days, there was hardly any enforcement. Fines were really small, and the few programs in existence were at the state level. I have seen the major legislation, the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act, and the rest, which have made a substantial difference in the environment. I have seen intractable problems become no less intractable. I have seen the complexity of the environmental field increase dramatically. The newest Clean Air Act is over 800 pages. The environmental regulatory system is becoming more and more ossified. It takes a longer period of time to enforce regulations. There are more regulations and there is more bureaucracy.

Finally, in recent years, I have seen the change to an entirely new set of paradigms: sustainable development; pollution prevention; use of nontraditional forms of environmental control, like market incentives and information; and integration of environmental concerns into policies across government agencies. We are seeing the change away from command and control, toward more flexible systems, and ultimately toward a decentralized system. It is hard to foresee this transition, but I think it is going to occur, and I would like to continue to be part of it, even if not in the government.

Q: Anything else to add?

MR. ALM: I cannot think of anything. No.

Q: Mr. Alm, I appreciate your time.

EPA 202-K-94-005

January 1994

Interview conducted by Dr. Dennis Williams on April 12, 1993 and June 23, 1993 at SAIC, Inc., McLean, Virginia