|

|

Reestablishing the Freshwater Unionid Population of Metzger Marsh,

Lake Erie

One of the most devastating ecological problems resulting from

the recent invasion of North America by zebra mussels (Dreissena

polymorpha) has been the virtual elimination of native clams or

unionids from infested waters. Zebra mussels readily colonize clam

shells, disrupting feeding, movement, and reproduction. Clams

generally die within 1-2 years after infestation. This die-off has

been well-documented in the Great Lakes (Schloesser and Nalepa,

1994; Schloesser et al. 1996), with near total mortality

reported throughout most of western Lake Erie. However, in 1996, we

discovered a large population of native clams in a western Lake Erie

wetland, Metzger Marsh, that showed little sign of infestation

despite zebra mussel colonization of the site since about 1990.

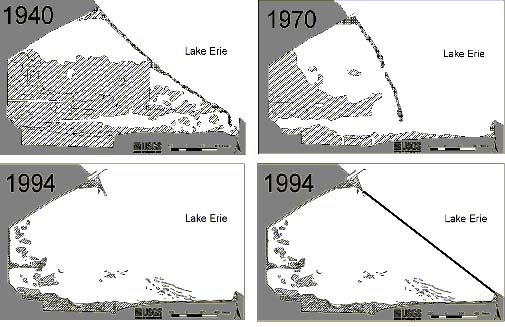

Metzger Marsh is a lake-connected wetland located 32 km east of

Toledo, Ohio. Prior to 1940, portions of this 367-ha site were diked,

actively farmed, and then abandoned and allowed to revert back to

wetlands (Figure 1). The wetland embayment was protected from storm

activity by a barrier beach, which gradually eroded as sediment

supply decreased due to progressive armoring of the shoreline of the

lake. By 1990, much of the original wetland had also eroded. In

1994, a consortium of federal, state, and private organizations

joined forces to restore the wetland and provide improved habitat

for fish and wildlife. A dike was constructed across the opening of

the embayment to mimic the protective function of the lost barrier

beach, with plans to dewater the wetland to promote seed germination

and growth of emergent plants. Following two years of drawdown, a

water-control structure was placed in the dike to mimic the natural

barrier opening and was opened to restore hydrologic connection with

the lake.

|

Figure 1.

Schematic of aerial photographs of Metzger Marsh, western Lake

Erie, showing the destruction of the barrier beach and

subsequent erosion of wetland vegetation between 1940 and

1994. Hatched areas represent patches of wetland

vegetation. The bottom drawing shows the location of the

artificial barrier beach built at the site. |

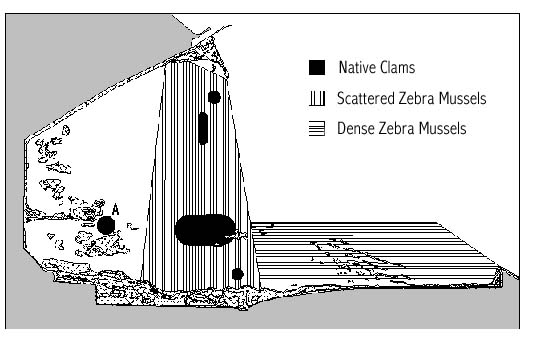

Surveys of the biota before construction of the dike identified a

large population of zebra mussels in the lakeward half of the site

(Figure 2). Two types of zebra mussel colonization occurred: 1)

extensive layers, several centimeters thick, totally covering the

substrate and 2) individual clusters of mussels limited to hard

structures such as logs, rocks, or vegetation. The area totally

covered by zebra mussels extended about 150 m by 300 m. Five live

unionids, representing two species, Quadrula quadrula and

Leptodea fragilis, were also found in the surveys. Since so few

live unionids were collected and the entire area was colonized by

zebra mussels, scientists involved in the project hypothesized,

based on best available information (Schloesser & Nalepa 1994) that

only a small remnant clam population was present. However, the

dewatering process later exposed a clam population far more

extensive than expected.

|

Figure 2.

Distribution of zebra mussels and thick-shelled unionids

collected from Metzger Marsh, western Lake Erie, 1996. "Dense

zebra mussels" refers to areas where extensive colony mats

covered the substrates and "scattered zebra mussels" to areas

where minimal substrate colonization occurred by all other

objects (vegetation, rocks, logs, etc.) were colonized with

the exception of the unionids. "A" marks the site where the

oldest and largest individuals of all species were collected.

|

About 7000 live unionids representing 20 species, including three

State of Ohio threatened species, and multiple year classes were

found during the dewatering (Table 1). Once this population was

discovered, a conglomerate of state and federal officials met to

decide what to do with these animals. To become a functioning

wetland, Metzger Marsh had to be dewatered first, a process which

would likely result in the destruction of the entire population. On

the other hand, the invasion of zebra mussels meant that release of

the unionids into Lake Erie proper would also result in their

destruction. This population was considered critical to the future

restoration of unionids in the western basin of Lake Erie, since it

is one of the few Lake Erie genetic stocks to have survived the

negative effects of zebra mussels. The Great Lakes Science Center

was charged with removing, boarding, and "doing something

appropriate" with these animals until they could be returned to

Metzger Marsh sometime in the future. In partnership with the EPA,

our primary goal was to salvage as much of the unionid fauna as

possible, and to use this fauna to ultimately rebuild the population

in Metzger Marsh.

|